WHAT

THE WORK CAN DO

For thoughts 8 months later, see "Artfulness of rendering spatial practice" tab in Thinking Through Practice page

This is precisely how I feel about my MA research-creation thesis,

Making space for deep mapping: rendering theory as praxis.

I am perpetually moved by negative-spaces as it works in excess of the zip folder submitted to

cIRcle. The sense of a work outdoing itself is what I wish to carry forward into my PhD. Without knowing yet

what form the staged dissertation will take, I am thinking about what makes any work of mine work—in

other words, I am considering "the question of how an artwork evolves to exceed its form, to create from its

force-of-form a more-than that can be felt, if not easily described" (Manning 201, 101). Research-creation is

about this more-than.

Reading process philosophy alongside J.K. Gibson-Graham and then tabling my artwork this term have urged me to

think about how research-creation complicates commodities, interfering with hegemonic discourses of value and

evaluation. Research-creation performatively reconfigures boundaries, and those defining the economies in

which research and creation operate/participate are no exception. While the research-creation of my MA thesis

was in conversation with Natalie Loveless' manifesto How to Make Art at the End of the World (2019),

since July of this year (2024) I have been moved by the language of Erin Manning:

Research-creation…understood not as an academic field but as practice, operative in the interstices of

making and thinking can, at its uncertain limit, connect to study [a term from Harney and Moten's The

Undercommons]. It can be a mode of inquiry that asks what (other) forms learning can take. It can

refuse to privilege the materiality of language over other forms of expression while at the same [sic]

recognizing thinking as a creative practice in its own right. When practiced this way, research-creation

creates the conditions to ask how the theory-practice split continues to give knowledge production a certain

linguistic overtone, understanding practice more as that which needs to be studied than as study itself…when

the work becomes the practice, when the practice invents its own language, research-creation deeply

threatens the power/knowledge that holds the academy in place. (Manning 2020, 221)

research-creation as a mode of activity all its own, occurring at the constitutive level of both art

practice and theoretical research, at a point before research and creation diverge into the institutional

structures that capture and contain their productivity and judge them by conventional criteria for added

value. At that prebifurcation level, making would already be thinking-in-action, and conceptualization a

practice in its own right. The two, we proposed, would intersect in technique, technique understood here as

an engagement with the modalities of expression a practice invents for itself… Experimental practice

embodies technique toward catalyzing an event of emergence whose exact lineaments cannot be

foreseen…Technique is therefore processual: it reinvents itself in the evolution of a practice. (Manning and

Massumi 2014, 89)

Erin Manning in For a pragmatics of the useless (2020)

Erin Manning in For a pragmatics of the useless (2020)

Erin Manning and Brian Massumi in Thought in the act (2014)

Erin Manning and Brian Massumi in Thought in the act (2014)

It is the "uncertain limit" of making and thinking, making as thinking-in-action, and "thinking as a creative

practice in its own right" that most interest me. The purpose of a Directed Reading (and doing) which spans

the first two terms of my PhD is to articulate what the work—taken as the multi-year endeavor of my PhD—can

do. My aim is to cultivate a research ethos that will guide my exploration and response to questions

coming out of MA and those developed in the first year (or so) of my PhD. As always, I practice diffractive

inquiry by thinking through practice and reading diffractively. Diffractive reading is about reading

through rather than against: interference rather than opposition, diffraction rather than reflection.

"Diffractive readings bring inventive provocations;" says Barad in an interview, "they are good to think with"

(van der Tuin and Dolphijn 2012). Drawing from Barad and Haraway, Murris and Bozalek (2019) develop

propositions to guide diffractive readings of literature. They caution:

The challenge in adopting diffraction as a methodology is not to theorise the diffraction pattern (a

logic of representation), but to put it into practice, thereby disrupting the theory/practice binary.

The idea is to read theory with practice diffractively guided by, for example, key questions that

move the experiment forward. (Murris and Bozalek 2019, 1505, emphasis in original)

Reading theory through practice, theorizing practice through practice, reading theories through one

another, and reading the effects of all this through the ever-refiguring questions which drive my

experimentation forwards is an approach I came to understand over the course of my MA (see

../interference.html#diffractive-reading).

The iteration on an output that follows will reflect on (some of) my creative practices over the past term

(the first term of my PhD program), what my work is doing so far, and articulate some

questions both old and new that continue to drive

my experimentation forwards. The output is both this page but also this space,

negative-spaces.github.io/the-middle-of-things/,

which I've created to gather and commemorate a partial, ongoing, and open-ended account of my process as it

unfolds.

WHAT

MATTERS NOT

This term I primarily read process philosophy in tandem with class readings for Economic Geography. Although I

found the class content rather dull, I did enjoy writing the final paper. It gave me a chance to work through

questions lingering in my thesis

negative-spaces.github.io/tactics.html

page, which asked: How does my participation (as both academic and urban

inhabitant) in unruly material and semiotic flows interfere with regulated forms of exchange from within the

dominant system? In emphasizing the ways in which my practices of everyday life poached capitalism

from within, constituting a "proliferating illegitimacy" that "elude[d] discipline without being outside the

field in which it is exercised…" (de Certeau 1984, 96), I struggled not to render capitalism omnipotent.

Indeed, Trevor wondered whether I hadn't rendered "the economy" a hegemony of its own. I therefore approached

my Economic Geography term paper as an opportunity to further explore the perhaps generative interrelation of

capitalist and noncapitalist practices, with specific attention to how my research-creation might participate

me in diverse economies. To this end, my paper critically assessed the contributions of J.K. Gibson-Graham

across three books: The End of Capitalism (As We Knew It) (1996), A Postcapitalist Politics

(2006), and Take Back the Economy (2013). (You can see the whole paper under

thinking through JK Gibson-Graham.)

I found writing this paper to be an exercise in faith: I knew there was an idea I wanted to think into through

the writing, but I couldn't rush it. I just had to write and trust my thinking to unfold in the process. My

job was to remain to make space for connections to happen, remaining open to the possible directions these

connections might take me. And it worked! This term I significantly upped my reading practice, as well as that

of writing and synthesizing my ideas in a clear and straightforward manner.

In sum, while I learned a lot from J.K. Gibson-Graham about capitolocentrism and diverse economies, I didn't

find their framework helpful in terms of probing the generative interrelation of capitalism and noncapitalism.

The boundaries of diverse economic practices were, in my opinion, all too tidy. Two entwined areas of

dissatisfaction emerged for me. First, in constructing and enacting a language of diverse economies, J.K.

Gibson-Graham center discourse as both site and instrument for subverting hegemonic fixations of meaning.

Discussion of materiality remains wholly unaddressed. A particularly compelling case for me was their

reframing of tools and practices of capitalist reproduction to those of noncapitalist production.

Gibson-Graham write: "What haunts the capitalist commodity is not only noncommodity production…but

noncapitalist commodity production…" (1996, 245, emphasis mine). "Remember that commodities are just

goods and services produced for a market, and that not all commodities are produced in capitalist enterprises"

(Gibson-Graham 2006, 68). Complicating the notion of households as merely sites of social reproduction, they

explicate how reproduction of the paid, capitalist workforce through unpaid and feminized labor subsumes what

could otherwise be rendered as a lively site of noncapitalist production under a discursive hegemony which

fixes capitalism's dominance. Take household appliances for example. Read through capitalism, household

appliances are capitalist commodities for consumption; they are goods purchased by families in order to be

used for social reproduction, that is, reproduction of the capitalist workforce through unpaid labor. Read

through the framework of diverse economies, however, household appliances come to matter as technologies of

noncapitalist commodity production (Gibson-Graham 1996, 31). This reframing, minor though it may seem,

challenges the impulse to immediately identify both labor and material by their relation to capitalism. Yet

I'm left wondering what the effects of such refiguration are, beyond dislodging a discourse of

capitolocentrism in favor of a counterhegemony of diverse economies. It seems that for J.K. Gibson-Graham, the

materiality of an appliance never changed, just the way it was discursively rendered. However, if we recognize

these refigurings as enacted by Baradian apparatuses (see Barad 2007, also

../interference.html#baradian-apparatuses)—those

ongoing and open-ended material-discursive boundary making practices which render the world differentially

intelligible—discursive reconfiguration is at once a

material reconfiguration with consequences that quite literally matter. What happens when gifted

materials intermingle with so-called commodities? What would it mean for a feminist political economy to

recognize, as Barad (2007) does, that "Knowing is a distributed practice that includes the larger material

arrangement" (342) "(i.e., the full set of practices) that is a part of the phenomenon investigated or

produced" (390)? How might we account for hauntings

materials inherit as they are discursively refigured?

Second, the more-than-human and the nonhuman are conspicuously absent across all three books. In a later paper, J.K. Gibson-Graham do consider the "interdependencies,[sic] between humans, environments and non-human entities… displac[ing] humans as the sole agents of ethical decision-making" (Roelvink and J.K. Gibson-Graham 2009, 151). However, their discussion remains focused on the ecological in terms of non-human nature; in thinking "the overdetermined process of production in a commodity economy" (Roelvink and J.K. Gibson-Graham 2009, 152), physical geography and nonhuman species are what comes to matter, not the nonhuman others of equipment and infrastructure. Is not a printer, left in an alleyway constituent of an urban ecology? What might a postcapitalist politics look like that doesn't presuppose the boundary between human and nonhuman? How might materiality be repoliticized within a diverse economy? My exploration of these questions connects back to J.K. Gibson-Graham's insufficient (nonexistent) attention to how materiality influences discourse. Karen Barad, whose posthumanist performativity extends both Butler and Foucault by attending to how matter itself comes to matter, views "materiality as an agentive and productive factor in its own right" (2007, 134). They ask: "Is there any sense in which materiality might be said to constrain discourses? If so, how? Do material reconfiguring have discursive consequences?" (Barad 2007, 225). An inversion of the last question—do discursive reconfigurings have material consequences?—applies to my reading of Gibson-Graham. I find these provocations infinitely generative to think with—intercessors (see Manning 2020) even, for research-creation in its attempt to fruitfully engage with J.K. Gibson-Graham's contribution to feminist political economy.

UNRULY

MATERIAL

One way to think (about) materiality is by considering how the way things are made participates them at once

in material and discursive economies. I want to

offer a speculative reading of what it might mean to account for the hauntings matters inherit as they

undergo material-discursive refigurings. I'll focus on a significant intra-locutor of mine with whom

I've been collaborating closely as of late: an Epson WorkForce Pro 4740 printer I gleaned in a Dunbar alleyway

soon after I moved to Vancouver. My printer serves two major functions. First, it enables me to print

hard-copies of class readings. I require hard-copies to read for many reasons which can most legibly be

summarized as "due to disability." Well, most legibly to the reader, not to the institution. Although I am

registered with UBC's Center for Accessibility, when I asked to be accommodated with hard-copy readings for

class I was told this request was not an accessibility need. My Epson WorkForce Pro 4740 printer has therefore

served as a tactic of self-accommodation in the face of UBC's disabling subjectivation (see

../rendering.html#sitation-as-ndstorying-tactic).

Second, I use my printer to craft cards, stickers, iron-on transfers, prints, bookmarks, zines, and more which

I gift freely and barter, as well as exchange at local art markets. The clothing I print on is material I've

salvaged for free from the fabric recycling dumpster in the basement of my building, as well as from alleyway

free boxes. I also make stickers of graffiti I follow around the city, re-siting these unruly

material-semiotics in perpetuation of a "proliferating illegitimacy" (de Certeau 1984, 96).

In the first case, that of assistive technology, my printer can by figured as a commodity in service of knowledge production under (academic) capitalism. In the second case, that of creative practice, my printer may be figured as a means of production for gift and barter economies, as well as for informal markets of alternate and reciprocal exchange. In both cases, I make use of ink and supplies obtained through appropriating institutional grants intended for "fieldwork" and "research materials". In the instance of both assistive technology and creative practice (for the boundary between the two disintegrated over the course of my inquiry), knowledge is generated in the very process (enterprise) of making (laboring) and distributing (transacting) my outputs. For instance, one person came back and asked if they could have a different set of cards because there was a faint line running through one of the prints they had just purchased. Taking a gracious "the customer is always right" approach, I said sure. After finding them untying and rifling through multiple sets of cards, I did intervene, saying what amounted to: the line is part of the art. Reflecting on this interaction afterwords with two friends, I realized how involving money in transaction opened the receiver's expectations in a capitalist mode. Money tuned the exchange, the receiver feeling entitled to a certain quality of product to the point where they'd request a return or exchange. Specifically, they expected a product which appeared untouched by human or machine. When that was not delivered, they did not feel their money was well spent. I also set all my goods at five or ten dollars each. While fellow tablers "nagged" me to raise my prices, I wasn't there to optimize my profit margin. (I was there as fieldwork and inspiration as much as anything. Yes, it was important to cover my production costs but beyond that, I felt my time was well spent reading the experience through Gibson-Graham and my making practices. My grand ambition is to table at Vancouver's Dyke March next summer.) Working with gleaned materials enabled me to set my prices low, and a couple people explicitly thanked me for making my artwork affordable and accessible. I even had an assortment of free stickers, and encouraged people to gift me their old t-shirts in exchange for my artwork in the future.

The interference I want to make here is this: drawing from posthumanist performativity, I suggest there is another way to materially and discursively configure appliances, one which gets us out of the capitalism/noncapitalism binary. What if, say, my printer was never wholly interpellated as either a commodity for reproducing (academic) capitalism or as a means of noncapititalist commodity production, but was instead c/sited as an intellecting other in its own right. Acknowledged as such, my printer could be recognized as continually gifting its capabilities in exchange for ink and paper. Material outputs are therefore imbricated with mainstream capitalist, alternative capitalist, and noncapitalist economies by virtue of input materials being bought in-store, appropriated from institutional grants, as well as salvaged, poached, and gleaned. Although J.K. Gibson-Graham acknowledge "The market is not all or only capitalist, commodities are not all or only products of capitalism" (1996, 144), discussion of the intertwining nature of capitalist and noncapitalist markets with capitalist and noncapitalist commodities—and noncapitalist noncommodities for that matter—is limited to a single paragraph in A Postcapitalist Politics (2006, 150). Gibson-Graham thus fail to consider things which are produced for market and nonmarket transactions simultaneously, let alone account for how the apparatuses which produce them might be conceptualized.

The creative artifacts of research-creation defy the easy delineation of commodities as goods and services

produced for markets. Whether the material outputs of research-creation are figured as gifts (and therefore

enrolled in nonmarket transactions) or bartered/traded/sold locally (enrolling them in alternative market

transactions) is less important to the project than what the material-discursive (or physical-conceptual, as I

prefer) work is doing and how boundaries are refigured as an effect. Therefore, "research-creation

participates in both the gift alter-economy and the dominant quantitative economy" (Manning and Massumi 2014,

130). The more-than of research-creation exceeds measure. When the work works, when it "continues to move you

beyond its staged iteration" and "dislodge the you that you thought you were" (Manning 2013, 102), it

generates value beyond evaluation. I mean this literally in the sense that institutional systems of rendering

knowledge production performatively legible as such do not as yet have ways of accepting graduate

research-creation and evaluating it on its own terms. I speak specifically to the case of UBC, where I

recently completed an MA in Geography. My interference praxis revealed that the technical system which renders

graduate submissions legible as knowledge will, as and through rule, subordinate creative artifacts beneath

linear text.pdf research outputs (see

../rendering.html).

This preference for (deference to) written language and the monograph is fundamentally at odds with

research-creation, which "ask[s] that multiple formal outputs be treated with equal value" (Loveless

2019, 115, emphasis in original). Contributions can still be research-creation, don't get me wrong. My

MA thesis was a research-creation thesis. However, in the process of making my form legible/intelligible to

the Public Scholarship Coordinator and Associate Director of Student Academic Services, I materially

experienced how the sociotechnical system of institutional (graduate) publishing is not set up to reckon with

the more-than—to see value in what a work is doing in excess of its form. Write Erin Manning and Brian Massumi

(2014): "research-creation as we propose to practice it is a polyrhythmic attuning of mutually composing

autonomous activities that collectively resist definitive capitalist capture and affirm value in terms that

cannot be quantified" (123). It is because research-creation offers something that cannot be measured and

therefore evaluated by current institutional standards and frameworks of intelligibility that it, at its most

generative, should be "understood not as an academic field but as practice…" (Manning 2020, 221).

Research-creation "deeply threatens the power/knowledge that holds the academy in place" (Manning 2020, 221)

because it is transgressive. Writes Barad, "Boundary transgressions should be equated not with the dissolution

of traversed boundaries (as some authors have suggested) but with the ongoing reconfiguring of boundaries"

(2007, 245). In my thesis, I elaborated how the boundary of an intelligible form is rendered articulate only

in its crossing (see

../rendering.html#negative-spaces);

indeed, "it is likely that transgression has its entire space in the line it crosses" (Foucault 1977, 34).

Only through conversing with representatives/constituents of UBC's Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral

Studies did the rule dictating creative artifacts of MA theses be submitted as secondary to linear

text.pdfs come into being. My interference of proposing an alternately figured thesis was therefore necessary

in order to illuminate where and how the university drew boundaries to secure certain forms of

intelligibility. (By interference, I do not mean a disruption that's inherently bad or negative but rather an

engagement through which boundaries take provisional shape and differences come to matter.) The practice of

research-creation involves both generating interferences and studying how the effects of interference come to

matter. In this way, research-creation is a diffractive methodology (Barad 2007, Barad in van der Tuin and

Dolphijn 2012, Murris and Bozalek 2019, see

my thesis). To be clear:

research-creation does not employ a diffractive methodology, it is a diffractive mode of inquiry.

I found J.K. Gibson-Graham's framework of diverse economies hence ill-equipped to consider economic practices and materialities that support capitalist production and reproduction while simultaneously subverting capitalocentrism. (Like, it felt as though cultivating ourselves as different (and differently desiring) economic subjects meant investing in noncapitalist economic practices without recognizing or embracing the way they sustain/substantiate one another?) In finally recognizing that "non-human others and non-labouring others are also implicated in the production and appropriation of surplus", Roelvink and Gibson-Graham (2009) give the example of farmland whose "'gifts'" are repaid in "unremunerated exploitation and degradation" (153, emphasis in original). My reading of so-called assistive technology offers something different, I think, in that my ethics of care is concerned with practices of receiving and acknowledging giftings of things which themselves (and their services) are irreducible to commodities. Moreover, recognizing my printer as actively gifting sites its materiality not fully within commodity capitalism, itself imbricated in the gift economy of alleyways. Operating on urban denizens’ tacit knowledge of the city, matters deemed no longer fit for manufactured purpose are offered up as open-ended invitations for recirculation by passersby. By "urban denizens tacit knowledge of the city" I mean practical knowledge of the way things work; a box of odds and ends put out on the curb or the edge of a lawn means passersby are welcome to take what they want. The gift economy of alleyways is therefore also entwined with consumer excess under commodity capitalism. (I once encountered a giant TV with a note: santa brought a bigger one.) Alleyways, curbsides, and free boxes become sites where use and value are refigured. My printer is more than an assistive technology or office appliance—it is an intra-locutor, an intellection other with whom I collaborate in the physical-conceptual crafting of worlds that is knowledge production.

THINKING

WITH INTELLECTING OTHERS

Engaging my printer as intra-locutor is a way of making explicit practices of thinking with nonhuman others. I

am reminded of Erin Manning's reading of Bracha Ettinger, an Israeli-French artist and psychoanalyst whose

Autistwork series crafts with found images and a scanner. Writes Erin Manning: "the photocopy machine is

itself a way of seeing-with, a collaborator in the processual fielding that is the autistwork" (2013, 182).

Ettinger's Autistwork series

demonstrates that the how of knowing much exceeds the what (and the who) of knowing…It makes

seen the constitutive difference between knowing-with and a more generalized knowing—knowing as

categorization, organization, representation. It reminds us that to know is to participate in a folding that

will remain an intensity too multiple, too ineffable and too indefinite to articulate without

composing-with. To know is to know-with—to participate in the creation of worlds, words churning with the

exquisite singular-infinity of eternal objects [conceptualized elsewhere as "a mechanism by which the actual

becomes more-than, expressing its latent potentiality" (176), "a quality of relation that holds the

seeing-with to the abyss of its eventful nonrepresentation" (180)], seeings-in-the-feeling that continuously

reinvent what perception (and knowing) can do. (Manning 2013, 181)

There is no isolated knowing, just as there is no composing alone. What if

marks of the way things were made (a printer line; uneven stitching) were embraced as part of the

artwork rather than error? Is there something about capitalism that devalues such traces? I want to broaden my practice of thinking with materiality that co-composes

my artworks to the Baradian apparatuses which create the conditions for my intra-action with them.

Baradian apparatuses, as mentioned above, are ongoing and opened-ended material-discursive boundary making

practices which resolve the indeterminacy of a property by performing an "agential cut" whereby the "agencies

of observation" and "object of observation" are differentially articulated. "Agencies of observation" and

"object of observation" are provisional configurations—entangled states which mark one another within and as

part of "phenomena". According to Barad's agential realism, "measured properties refer to phenomena…"

(Barad 2007, 197, emphasis in original). The agential cut performed by an apparatus is what differentiates

agencies of observation and object of observation, thereby producing the condition of exteriority within a

phenomenon. It is through this exteriority within phenomena that a casual structure emerges where

"measuring agencies" ("effect") are marked by the "measured object" ("cause") (Barad 2007, 337-340). Put

another way, "measurement is the intra-active marking of one part of a phenomenon by another" (Barad

2007, 388, emphasis in original). Because "measured values can be unambiguously and contingently attributed to

the corresponding property of "objects-in-the-phenomenon" (not to some presumably independent object)" (Barad

2007, 465), the recorded value of a measurement is an objective reading if and only if its referent is a

phenomenon. Objectivity, Barad therefore avers, is not gained from a distanced, exterior position but from the

agential separability enacted by 'intra-actions' within phenomena. connect to composing with (later connect to

data, empirics, etc.) could even talk about camera here.

Research-creation as a practice of feeling, thinking, knowing, and composing with requires novel

citational practices for acknowledging intellecting others. Citation cites interaction: the

intellectual engagement of two presupposed human interlocutors who existed as independent entities before

their encounter. In my MA thesis, I began to theorize sitation as an alternative boundary making

practice to citation, one which recognizes artworks as phenomena wherein collaborators intra-actively mark one

another (see

../rendering.html#sitation).

Sitation assumes agencies and object of investigation to be provisional configurations where encounter's

formal acknowledgement within an academic work renders intra-locutors differentially determinate. Whereas citations cite interactions, sitations site

intra-actions. Sitations are diffraction patterns marking the effects of "differential

intra-actions" (Barad 2007). Sitations are therefore both sites and tactics of interference. Sitation

offers a way of "explicitly valorizing the collective webs one thinks with" (Puig de la Bellacasa 2012,

202). Critically, sitational practice "create[s] an environment where

knowing as final act is not the aim…Where what is remembered is how we came to a thought" (Manning

and Bozalek 2024, 4, emphasis in original).

site x thoughts on siting distributed knowledge production, walking under granville bridge loop

Friday, December 20th, 2024

The brevity and potential of my practices of acknowledging intellecting others sunk in over the past week as I recognized sitation could address the question, raised by my reading of J.K. Gibson-Graham, of how to account for the hauntings matters inherit as they undergo physical-conceptual (material-discursive) refigurings. My nascent suggestion is resitation. Future iterations will draw from posthumanist performativity to theorize resitation more fully. For now, I contend with the comings into thought experienced recently.

To celebrate the conclusion of my thesis in August 2024, I hosted a dinner party at the end of November. At the party, I read an excerpt from my thesis aloud and answered questions about my research-creation. I also prepared sitations from my thesis in the form of stickers (see above) which I encouraged people to take and re-site around the city in perpetuation of a "proliferating illegitimacy" (de Certeau 1984, 96). I had already begun doing this with FIND THE DRIFT/CROSS THE FENCE/REPORT ALL SIGNS a year or more ago.

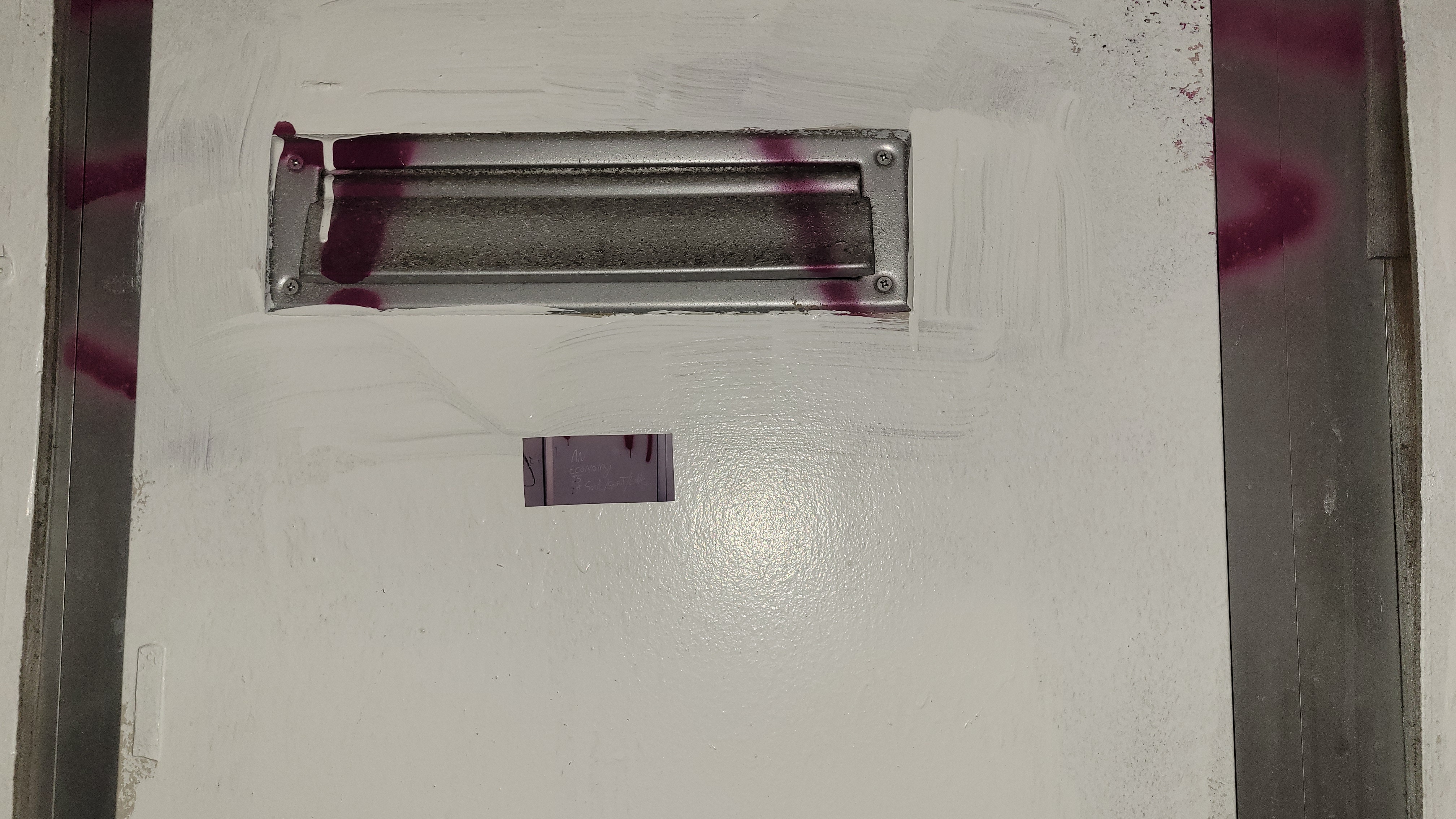

On a walk to Green's grocer Thursday I passed the vacant storefront where earlier this year (February 2024),

the graffiti "An Economy is a Soul/Spirit/Love" had inspired a conference paper and then the tactics page of

my thesis (see

negative-spaces.github.io/tactics.html).

This month (December 2024), the whole wall was painted over with thick white paint. I had leftover sitations

in my pocket and added one of the configuration of the wall I encountered to the now painted-over surface.

Thinking with this act, I began to wonder what resitation was doing.

The next day I decided to do this intentionally to a sitation made under the ramp of Granville Bridge which runs closest to where I live. There's this electrical substation there (the Fir Street Rectifier Station) with weathered green walls. Around its base, large swatches are painted in different hues of turquoise. I printed cards with this sitation earlier in the summer. This fall, I noticed someone had added abstract line-art over one of these swatches with earth and organic matter. It's really beautiful and creative and like nothing I've encountered before. I went down yesterday and added a sticker of a figuration from a different time.

add audio too

add audio too

In preparation for my round-table participation in the Urban Affairs Conference to be held in Vancouver this spring, I want to further elaborate sitation and resitation through urban graffiti literature. Only towards the very end of my thesis writing did I encounter people like Konstantinos Avramidis and Sabina Andron, both doing neat investigations into urban surfacing.

I also want to diffract resitation through my already agential realist theorization of sitation, as I think this will really challenge me to explore the limits of what a concept can do. As diffraction patterns marking the effects of differential intra-actions, sitations are are part of the phenomena they acknowledge. Remember: diffraction phenomena may at times be the object of investigation, whereas at other times, the apparatus of investigation, though never both at once (Barad 2007, 73). This is because to study an apparatus from a position exterior to the phenomenon within which it operates requires building an auxiliary apparatus, therefore "constitut[ing] the formation of some new phenomenon" (Barad 2007, 347) wherein the original apparatus of investigation is now the object of investigation. I suggest resitation could be an auxiliary apparatus with which to study sitations. Or, more specifically, auxiliary apparatuses to site sitational hauntings matters inherit as they undergo physical-conceptual refigurings from phenomenon to phenomenon. Resitations are non-exhaustive. As Baradian apparatuses, they are are non-hierarchical or non-nested, meaning each one configures relations in just such a way without forclosing the possibility of different cuts creating the conditions for relations that bear no resemblance or continuity to current delineations. I believe an exploration of the above will help me decide whether to keep, refigure, or discard two loaded questions coming out of my master's encounter with speculative data: How are empirics made legible as data by the apparatuses that produce them? How are technoscientific and affective orientations to ‘what counts as data’ co-constitutive of an empirical account of the city?

Someone whose work on speculative data speaks directly to this is my co-supervisor, Luke Bergmann. In his article "Toward speculative data: 'geographic information', situated knowledges, vibrant matter, and relational spaces", Bergmann (2016) discusses how Cartesian inflected data structures such as tables enable and constrain relations between properties in a manner reifying a "world of ontologically self-sufficient entities" (976). He asks: "How else might we constitute data—or even, how might we 'data' differently?" (976). Though I've just recently encountered others (predominantly in education, interestingly) doing data differently (see, for instance, Mirka Koro, Niki Fairchild), I find Bergmann's early contribution to speculative data particularly interesting for its focus on geographic information, or spatial data. Thinking with commitments to situated knowledges informed by Haraway, he asks another trenchant question: "Can geographic information be constituted not just as essentialized truth but as provisional, partial, and emergent within a dynamic web of interpretive practice?" (976). He goes on to expand the notion of a geo-atom, which Goodchild et al. define as a "tuple <x, Z, z(x)> where x defines a point in space-time, Z identifies a property, and z(x) defines the particular value of the property at that point" (Goodchild et al. 2007 qtd. in Bergmann 2016, 977), to a geo-interpretation, "< x, Z, z(x,r), r, s>, where r situates the data in terms of authors, claimants, observers, subjects or readers and acknowledges the interpretive nature of the information according to the context of its reception" (977) and s "would allow a place for reflexivity on the part of the creator of the datum" (978). Geo-interpretation "allow[s] for a web of iterative interpretation, leaving traces within the unfolding geographic information itself" These traces of iterative interpretation and sitation are what resitation is interested in studying. Excitingly, "allow[ing] that which is being interpreted its own history, its own complex of intensities, its own capacity for having had a variety of different interactions that were influential in its constitution, and different potentials for future interactions" (Bergmann 2016, 979) is a possibility opened up by geo-encounters. I imagine geo-interpretations and geo-encounters may be of relevance to creating, assembling, organizing, etc. "data" layers for a destination disoriented navigational application. While I'm working through what's laid out in the paper, I sense a connection to sitation and resitation. Perhaps sitation is a way of siting geo-interpretations, whilst resitation sites geo-encounters? Or maybe the relationship is not so direct or 1:1. Regardless, sitation and resitation in terms of research-creation is definitely something to ponder further in conversation with new materialisms, posthumanist performativity, graffiti studies, and experimentations in speculative data.