Adams, Paul C., and Jacek Kotus. 2022. “Place Dialogue.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (4): 1090–1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12554.

Andron, Sabina. 2016. “Interviewing Walls: Towards a Method of Reading Hybrid Surface Inscriptions.” In Graffiti and Street Art, edited by Konstantinos Avramidis and Myrto Tsilimpounidi. Routledge.

Avramidis, Konstantinos. 2023. “Place Writing, Site Drawing: Researching Graffiti as a Critical Spatial Practice.” In The Routledge Handbook of Urban Design Research Methods. Routledge.

Barad, Karen. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Bauder, Harald. 2006. “Learning to Become a Geographer: Reproduction and Transformation in Academia.” Antipode 38 (4): 671–79. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8330.2006.00469.x.

Boren, Ryan. 2022. “Kinetic Cognitive Style.” Stimpunks Foundation. June 13, 2022. https://stimpunks.org/glossary/kinetic-cognitive-style/.

de Certeau, Michel. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Elliott, Denielle, and Dara Culhane, eds. 2017. A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. North York, Ontario, Canada ; Tonawanda, New York, USA: University of Toronto Press.

Foucault, Michel. 1977. “Intellectuals and Power: A Conversation between Michel Foucault and Gilles Deleuze.” In Language, Counter-Memory, Practice: Selected Essays and Interviews, edited by Donald Bouchard, translated by Donald Bouchard and Sherry Simon, 205–17. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press.

Gaza Academics and Administrators. 2024. “Open Letter by Gaza Academics and University Administrators to the World.” Al Jazeera. May 29, 2024. https://www.aljazeera.com/opinions/2024/5/29/open-letter-by-gaza-academics-and-university-administrators-to-the-world.

Gibson-Graham, J. K. 2008. “Diverse Economies: Performative Practices for ‘Other Worlds.’” Progress in Human Geography 32 (5): 613–32. https://doi.org/10.1177/0309132508090821.

Hawkins, Harriet, Lou Cabeen, Felicity Callard, Noel Castree, Stephen Daniels, Dydia DeLyser, Hugh Munro Neely, and Peta Mitchell. 2015. “What Might GeoHumanities Do? Possibilities, Practices, Publics, and Politics.” GeoHumanities 1 (2): 211–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/2373566X.2015.1108992.

“How To Create an Image Grid.” 2023. W3Schools. 2023. https://www.w3schools.com/howto/howto_js_image_grid.asp.

Huybrechts, Eric. 2013. “Chuuuttt!” August 1, 2013. https://www.flickr.com/photos/15979685@N08/11277600556/.

“Interview de Jef Aérosol Pour Son Autoportrait Chuuuttt à Beaubourg.” 2019. Autour de Paris. October 3, 2019. https://autour-de-paris.com/project/interview-jef-aerosol-autoportrait-beaubourg-fresque-chuuuttt.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2013. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Gerald Moore and Stuart Elden. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350284838.

Meekosha, Helen. 2011. “Decolonising Disability: Thinking and Acting Globally.” Disability & Society 26 (6): 667–82. https://doi.org/10.1080/09687599.2011.602860.

Mott, Carrie, and Daniel Cockayne. 2017. “Citation Matters: Mobilizing the Politics of Citation toward a Practice of ‘Conscientious Engagement.’” Gender, Place & Culture 24 (7): 954–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/0966369X.2017.1339022.

Murris, Karin, and Vivienne Bozalek. 2019. “Diffracting Diffractive Readings of Texts as Methodology: Some Propositions.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (14): 1504–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1570843.

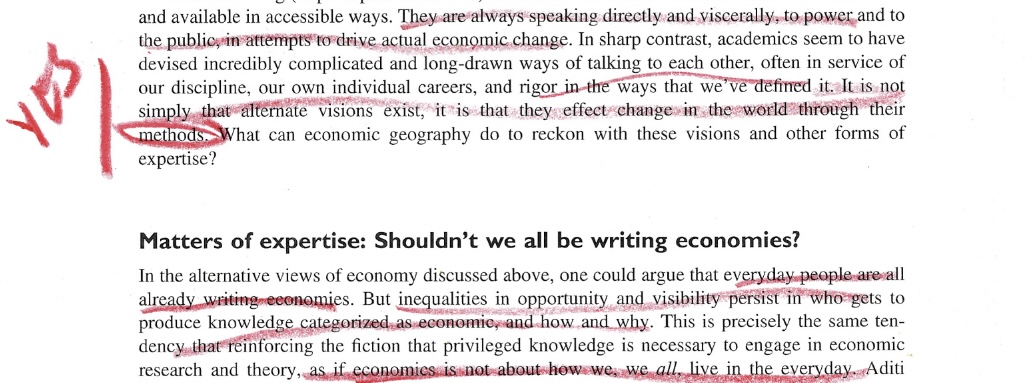

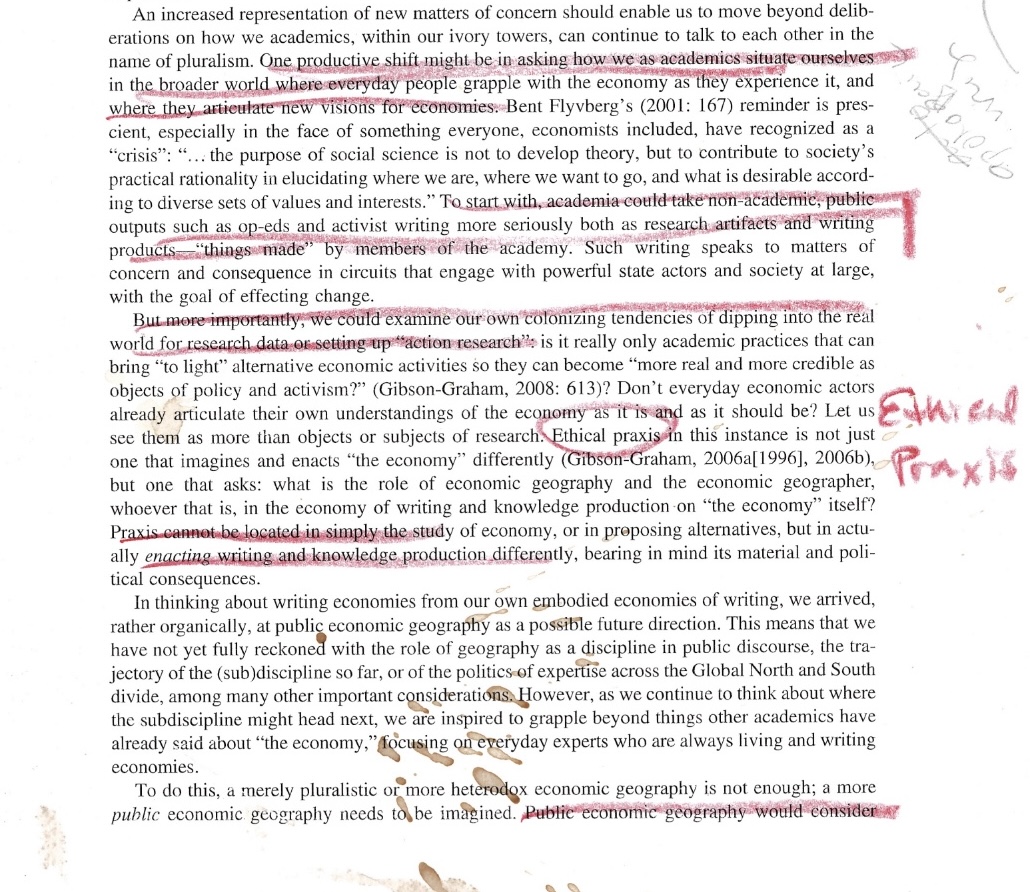

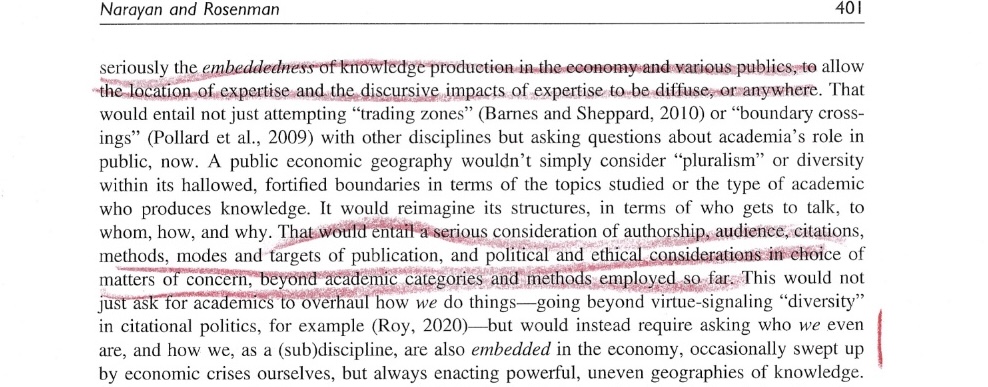

Narayan, Priti, and Emily Rosenman. 2022. “From Crisis to the Everyday: Shouldn’t We All Be Writing Economies?” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 54 (2): 392–404. https://doi.org/10.1177/0308518X211068048.

Paasi, Anssi. 2005. “Globalisation, Academic Capitalism, and the Uneven Geographies of International Journal Publishing Spaces.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 37 (5): 769–89. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3769.

Puar, Jasbir K. 2017. The Right to Maim: Debility, Capacity, Disability. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822372530.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2012. “‘Nothing Comes Without Its World’: Thinking with Care.” The Sociological Review 60 (2): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x.

Roberts, Les. 2018a. Spatial Anthropology: Excursions in Liminal Space. Rowman and Littlefield.

———. 2018b. “Spatial Bricolage: The Art of Poetically Making Do.” Humanities 7 (2): 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020043.

Scott, James. 1998. “Thin Simplifications and Practical Knowledge: Mētis.” In Seeing Like a State, 309–41. Yale University Press. https://yalebooks.yale.edu/9780300078152/seeing-like-a-state.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth Adams. 2018. “Writing Post Qualitative Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry 24 (9): 603–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417734567.

“Stravinsky Fountain.” 2024. Wikipedia. January 7, 2024. https://en.wikipedia.org/w/index.php?title=Stravinsky_Fountain&oldid=1194153938.

Tuin, Iris van der, and Nanna Verhoeff. 2022. Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities. Rowman & Littlefield. https://rowman.com/ISBN/9781538147733/Critical-Concepts-for-the-Creative-Humanities.

“UBC Faculty Response to Scholasticide in Palestine.” n.d. Google Docs. Accessed June 13, 2024. https://docs.google.com/forms/d/e/1FAIpQLScwMc1I6ovyrJorC1YxFEk5_UQKp4kHfy9xG6gjep93Siodcw/viewform?usp=embed_facebook.

“UN Experts Deeply Concerned over ‘Scholasticide’ in Gaza.” 2024. United Nations The Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. April 18, 2024. https://www.ohchr.org/en/press-releases/2024/04/un-experts-deeply-concerned-over-scholasticide-gaza.

site 1 In the above image, garbage overflows from two green commercial dumpsters. Spilling from torn bags, various containers and food waste litter the asphalt as crows perch amid the detritus. The photograph was captured by the author in alleyway in the West End of Vancouver on a Christmas Day walk, 2023. The below audio recordings below were taken in May 2022. Edit to the second recording: Bombus impatiens is not Quinn's favorite bee but a favored bee of study.

site 1 In the above image, garbage overflows from two green commercial dumpsters. Spilling from torn bags, various containers and food waste litter the asphalt as crows perch amid the detritus. The photograph was captured by the author in alleyway in the West End of Vancouver on a Christmas Day walk, 2023. The below audio recordings below were taken in May 2022. Edit to the second recording: Bombus impatiens is not Quinn's favorite bee but a favored bee of study.

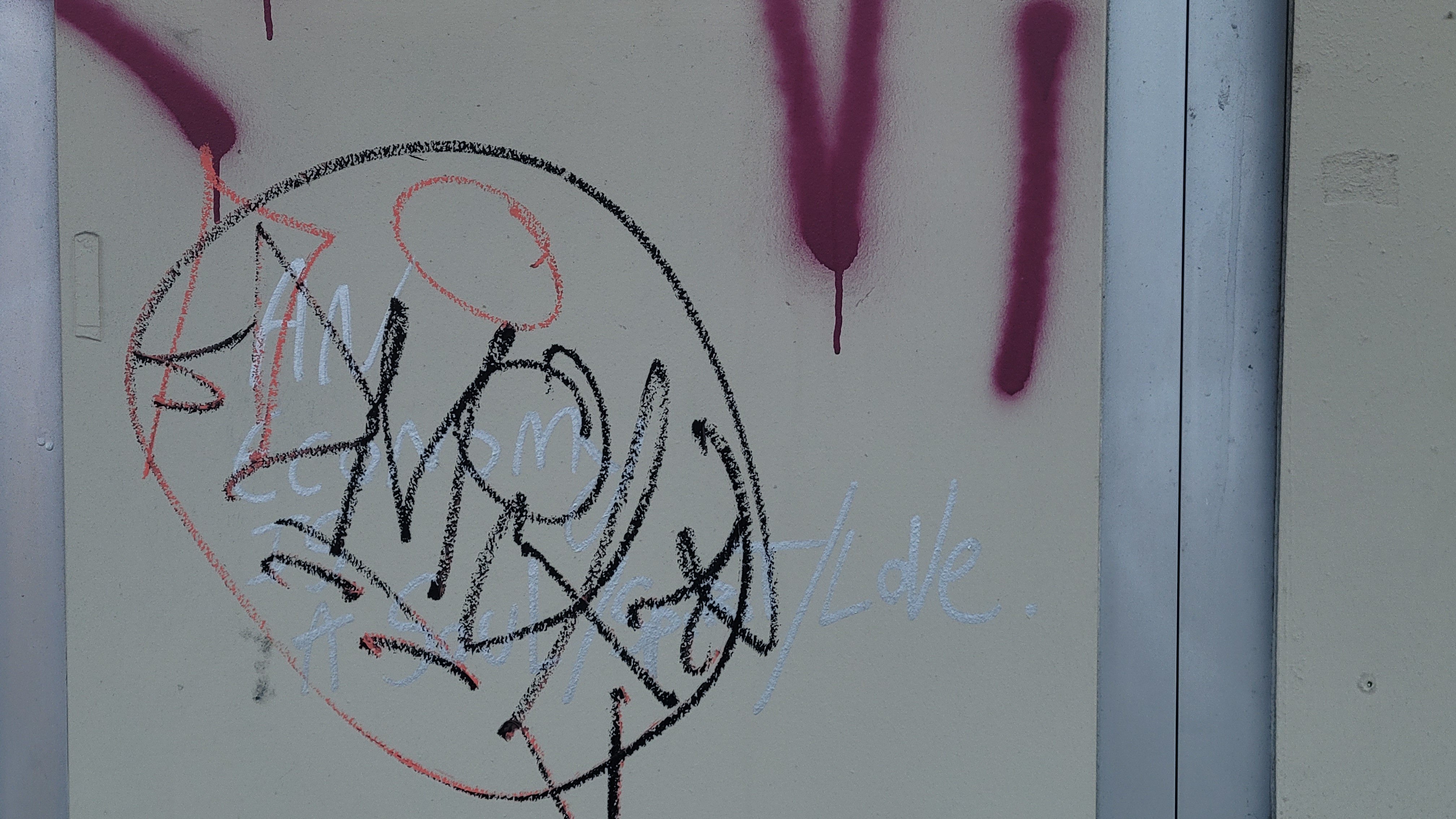

site 4 A municipal electrical box is covered in colorful graffiti.

site 4 A municipal electrical box is covered in colorful graffiti.

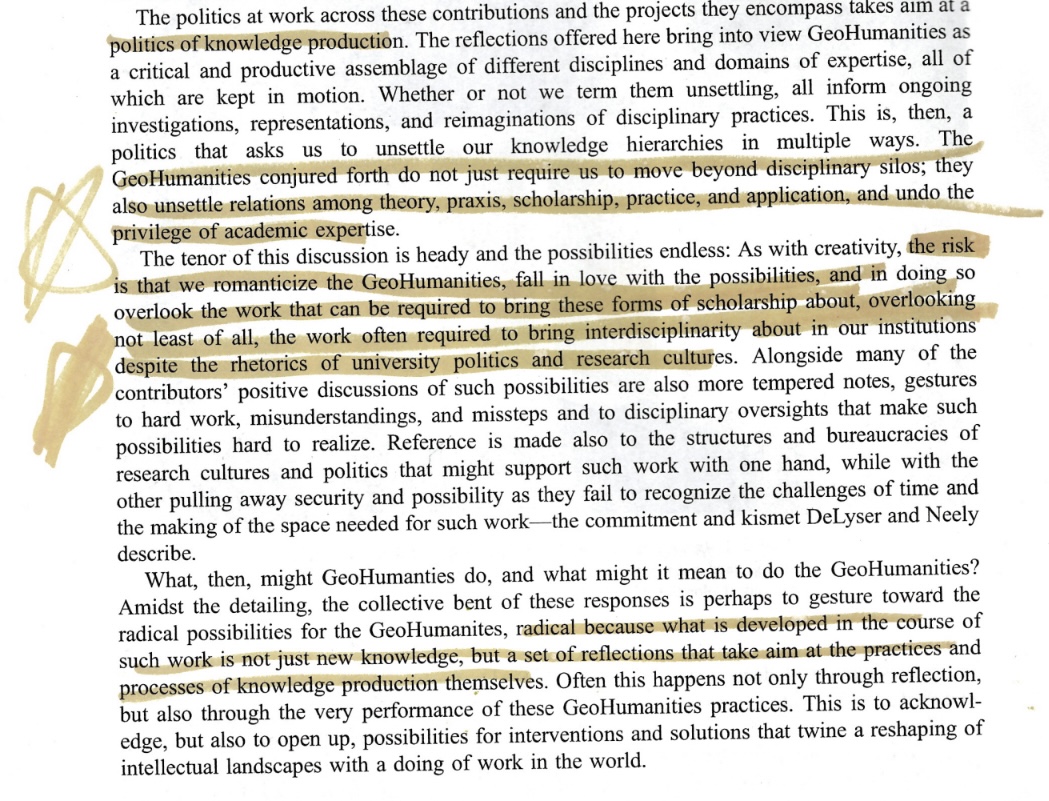

site 11 marked up page from Hawkins, Harriet, Lou Cabeen, Felicity Callard, Noel Castree, Stephen Daniels, Dydia DeLyser, Hugh Munro Neely, and Peta Mitchell. 2015. “What Might GeoHumanities Do? Possibilities, Practices, Publics, and Politics.” GeoHumanities 1 (2): 211–32.

site 11 marked up page from Hawkins, Harriet, Lou Cabeen, Felicity Callard, Noel Castree, Stephen Daniels, Dydia DeLyser, Hugh Munro Neely, and Peta Mitchell. 2015. “What Might GeoHumanities Do? Possibilities, Practices, Publics, and Politics.” GeoHumanities 1 (2): 211–32.