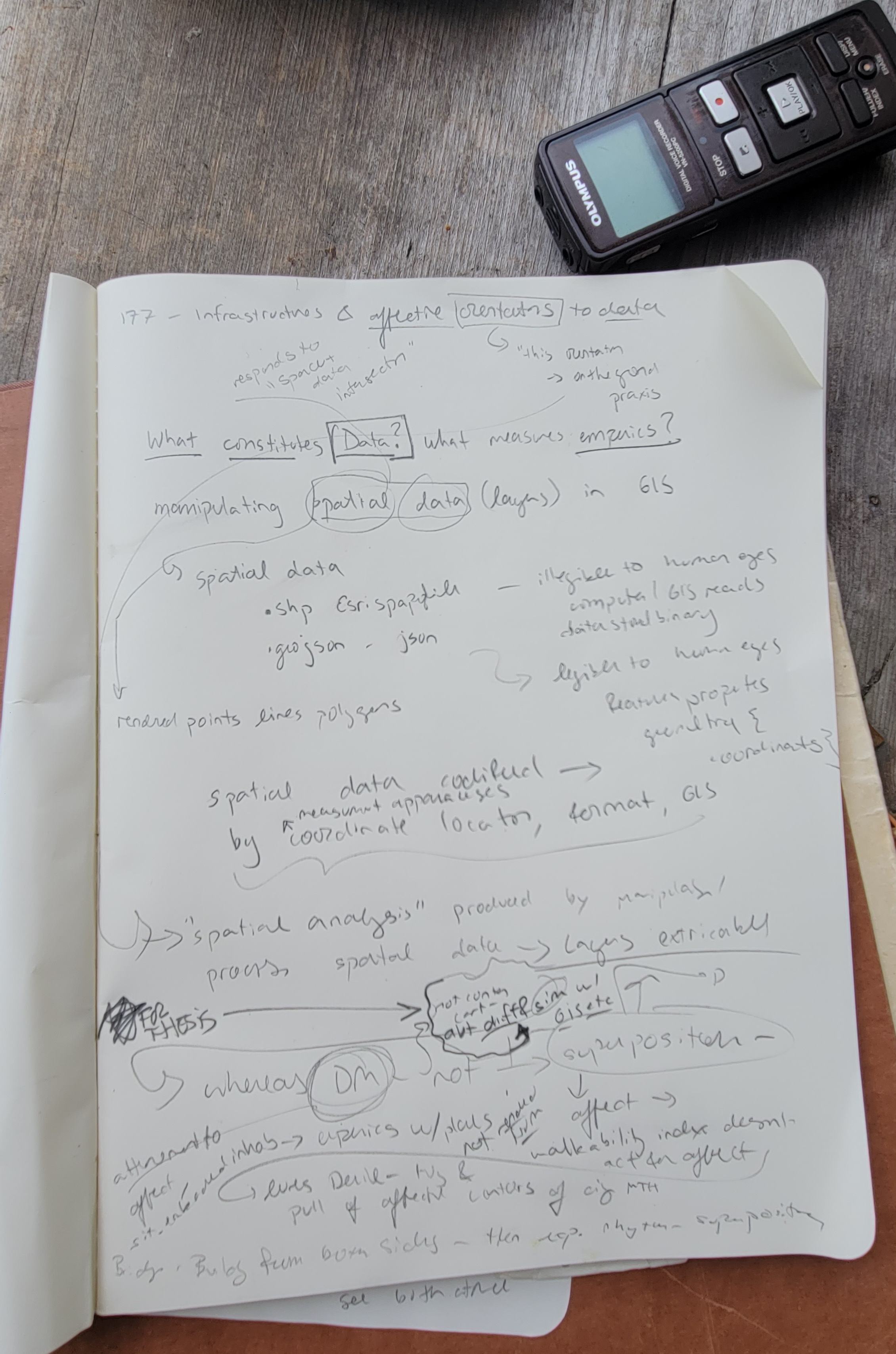

“177. Infrastructures and Affective Orientations of Data.” 2023. 2023. https://4sonline.org/news_manager.php?page=31520.

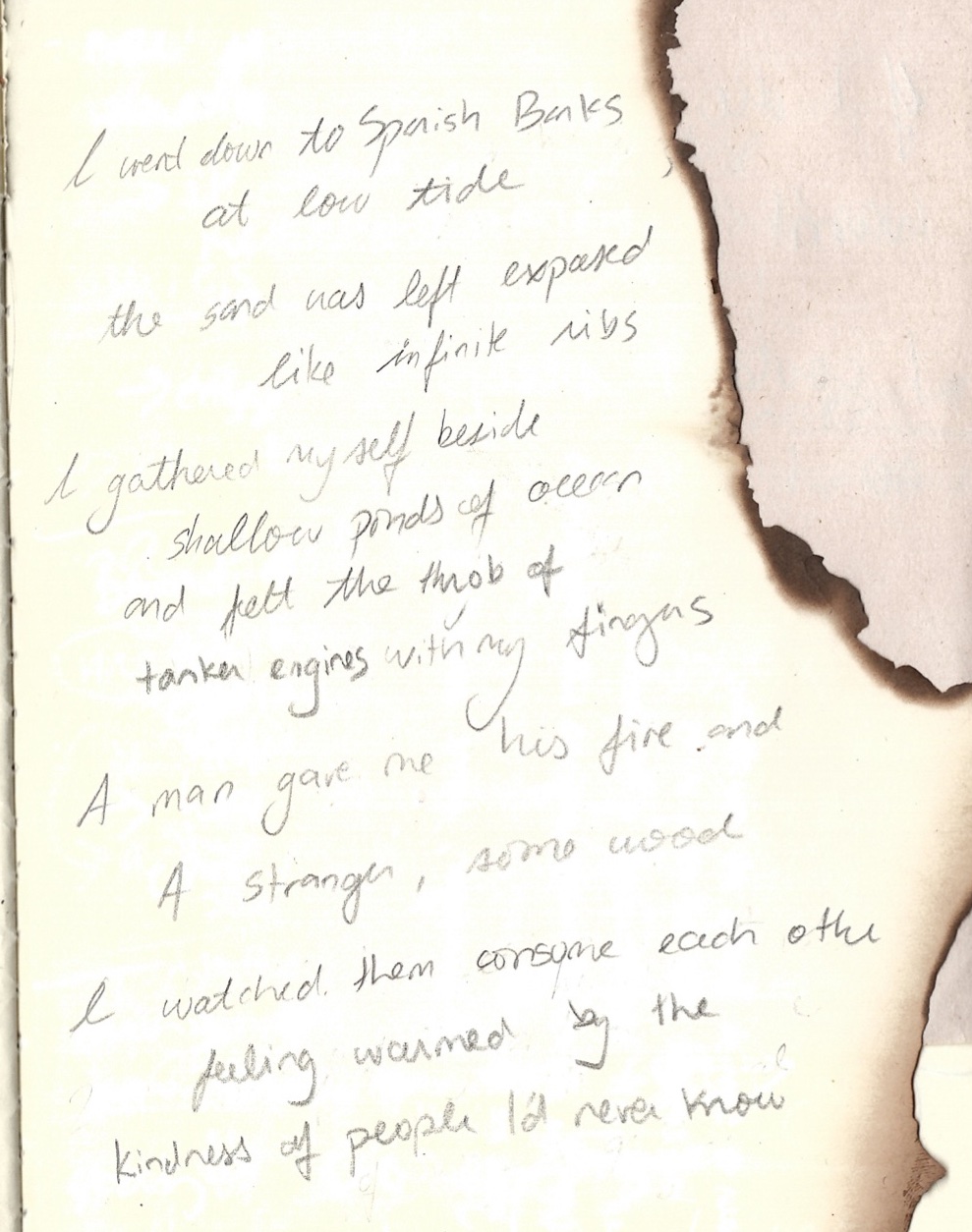

Acker, Maleea. 2019. “Lyric Geography.” In Geopoetics in Practice, edited by Eric Magrane, Linda Russo, Sarah de Leeuw, and Craig Santos Perez, 131–62. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429032202-10.

Adams, Paul C., and Jacek Kotus. 2022. “Place Dialogue.” Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 47 (4): 1090–1103. https://doi.org/10.1111/tran.12554.

Barad, Karen. 2003. “Posthumanist Performativity: Toward an Understanding of How Matter Comes to Matter.” Signs 28 (3): 801–31. https://doi.org/10.1086/345321.

———. 2007. Meeting the Universe Halfway: Quantum Physics and the Entanglement of Matter and Meaning. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

———. 2012. “On Touching—the Inhuman That Therefore I Am.” Differences 23 (3): 206–23. https://doi.org/10.1215/10407391-1892943.

———. 2014. “Diffracting Diffraction: Cutting Together-Apart.” Parallax 20 (3): 168–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13534645.2014.927623.

———. 2015. “Transmaterialities: Trans*/Matter/Realities and Queer Political Imaginings.” GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies 21 (2): 387–422.

Biggs, Iain. 2010. “Deep Mapping as an ‘Essaying’ of Place.” 2010. http://www.iainbiggs.co.uk/text-deep-mapping-as-an-essaying-of-place/.

Bissell, Laura, and David Overend. 2015. “Regular Routes: Deep Mapping a Performative Counterpractice for the Daily Commute.” Humanities 4 (3): 476–99. https://doi.org/10.3390/h4030476.

Bodenhamer, David J., John Corrigan, and Trevor M. Harris, eds. 2015. Deep Maps and Spatial Narratives. The Spatial Humanities. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

———, eds. 2021. Making Deep Maps: Foundations, Approaches, and Methods. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780367743840.

Certeau, Michel de. 1984. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Cogverse Academy, dir. 2016. 27 Interference & Diffraction - Thin Film Interference. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vxh0yjw4Z8I.

Cresswell, Tim. 2019. “Writing Place.” In Maxwell Street: Writing and Thinking Place, 1–20. University of Chicago Press. https://doi.org/10.7208/9780226604398-002.

Crouch, David. 2003. “Spacing, Performing, and Becoming: Tangles in the Mundane.” Environment and Planning A: Economy and Space 35 (11): 1945–60. https://doi.org/10.1068/a3585.

———. 2010. “The Play of Spacetime.” In Flirting with Space: Journeys and Creativity, 63–81. Ashgate Pub. Co.

Culhane, Dara. 2017. “Sensing.” In A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies, edited by Denielle Elliott and Dara Culhane. North York, Ontario, Canada ; Tonawanda, New York, USA: University of Toronto Press.

Cyca, Michelle. 2024. “Vancouver’s New Mega-Development Is Big, Ambitious and Undeniably Indigenous.” Maclean’s. March 11, 2024. https://macleans.ca/society/sen%cc%93a%e1%b8%b5w-vancouver/.

Elliott, Denielle, and Dara Culhane, eds. 2017. A Different Kind of Ethnography: Imaginative Practices and Creative Methodologies. North York, Ontario, Canada ; Tonawanda, New York, USA: University of Toronto Press.

Emerson, Robert M., Rachel I. Fretz, and Linda L. Shaw. 2011. Writing Ethnographic Fieldnotes, Second Edition. Chicago Guides to Writing, Editing, and Publishing. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. https://press.uchicago.edu/ucp/books/book/chicago/W/bo12182616.html.

England, Sara Nicole. 2018. “Filling in the Blank Spaces Through the Eyes of Exhibition Coordinator Sara England.” Initiative for Indigenous Futures. 2018. https://indigenousfutures.net/archive/filling-in-the-blank-spaces-through-the-eyes-of-exhibition-coordinator-sara-england/.

———. 2019. “Lines, Waves, Contours: (Re)Mapping and Recording Space in Indigenous Sound Art.” Public Art Dialogue 9 (1): 8–30. https://doi.org/10.1080/21502552.2019.1571819.

“Google Maps.” n.d. Google Maps. Accessed October 17, 2023. https://www.google.com/maps/search/disorientation/@49.2564613,-123.1824201,12z?entry=ttu.

Greenhough, Beth. 2011. “Vitalist Geographies: Life and the More-Than-Human.” In Taking-Place: Non-Representational Theories and Geography. Routledge.

Halberstam, Jack. 2013. “The Wild Beyond: With and For The Undercommons.” In The Undercommons: Fugitive Planning and Black Study, by Fred Moten and Stefano Harney. Wivenhoe: Minor Compositions.

Haraway, Donna. 1988. “Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective.” Feminist Studies 14 (3): 575–99. https://doi.org/10.2307/3178066.

———. 1991. “The Promises of Monsters: A Regenerative Politics for Inappropriate/d Others.” In Cultural Studies, edited by Lawrence Grossberg, Cary Nelson, and Paula Treichler. Routledge.

“History of the Sen̓áḵw Lands.” 2024. Sen̓áḵw. 2024. https://senakw.com/history.

Kurgan, Laura. 2013. Close up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics. First hardcover edition. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books.

Lefebvre, Henri. 2013. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Gerald Moore and Stuart Elden. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350284838.

Loveless, Natalie. 2019. How to Make Art at the End of the World: A Manifesto for Research-Creation. Duke University Press.

Magrane, Eric. 2020. “Climate Geopoetics (the Earth Is a Composted Poem).” Dialogues in Human Geography 11 (1): 8–22. https://doi.org/10.1177/2043820620908390.

Magrane, Eric, Linda Russo, Sarah de Leeuw, and Craig Santos Perez, eds. 2019. Geopoetics in Practice. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/Geopoetics-in-Practice/Magrane-Russo-deLeeuw-SantosPerez/p/book/9780367145385.

Manning, Erin. 2016. The Minor Gesture. Duke University Press. https://doi.org/10.1215/9780822374411.

Mason-Deese, Liz. 2020. “Countermapping.” International Encyclopedia of Human Geography, 423–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-08-102295-5.10527-X.

Modeen, Mary, and Iain Biggs. 2020. Creative Engagements with Ecologies of Place: Geopoetics, Deep Mapping and Slow Residencies. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003089773.

Murris, Karin, and Vivienne Bozalek. 2019. “Diffracting Diffractive Readings of Texts as Methodology: Some Propositions.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 51 (14): 1504–17. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2019.1570843.

Puig de la Bellacasa, María. 2012. “‘Nothing Comes Without Its World’: Thinking with Care.” The Sociological Review 60 (2): 197–216. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-954X.2012.02070.x.

Roberts, Les, ed. 2016a. Deep Mapping. Basil: MDPI AG – Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. https://doi.org/10.3390/books978-3-03842-166-5.

———. 2016b. “Deep Mapping and Spatial Anthropology.” Humanities 5 (1): 5. https://doi.org/10.3390/h5010005.

———. 2018a. Spatial Anthropology: Excursions in Liminal Space. Rowman and Littlefield.

———. 2018b. “Spatial Bricolage: The Art of Poetically Making Do.” Special Issue, Humanities 7 (2): 43. https://doi.org/10.3390/h7020043.

Springett, Selina. 2015. “Going Deeper or Flatter: Connecting Deep Mapping, Flat Ontologies and the Democratizing of Knowledge.” Humanities 4 (4): 623–36. https://doi.org/10.3390/h4040623.

St. Pierre, Elizabeth Adams. 2018. “Writing Post Qualitative Inquiry.” Qualitative Inquiry 24 (9): 603–8. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800417734567.

———. 2021a. “Post Qualitative Inquiry, the Refusal of Method, and the Risk of the New.” Qualitative Inquiry 27 (1): 3–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800419863005.

———. 2021b. “Why Post Qualitative Inquiry?” Qualitative Inquiry 27 (2): 163–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077800420931142.

“The Burnaby Refinery.” 2023. Parkland. 2023. https://www.burnabyrefinery.ca.

Towards a Practice of Decolonial Listening: Sounding the Margins | Candice Hopkins. 2019. President’s Dream Colloquium. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=vt1SBjDCJco.

Tuin, Iris van der, and Rick Dolphijn. 2012. “3. ‘Matter Feels, Converses, Suffers, Desires, Yearns and Remembers’: Interview with Karen Barad.” In New Materialism: Interviews & Cartographies. Open Humanities Press. https://doi.org/10.3998/ohp.11515701.0001.001.

“Visit Maplewood Flats.” 2024. Wild Bird Trust of British Columbia. 2024. https://wildbirdtrust.org/visit-maplewood-flats/.