DISORIENTATION

I have come to understand being a geographer as less of an ability to know where you are in space at all times and more as a capacity to learn through disorientation. Like many colleagues, I began graduate school in a place I’d never been before and where I didn’t really know anyone. In the midst of a global pandemic, I left rural Maine in the northeast corner of the United States — where I'd been isolating for a year — and began driving west. For the first time in my life, I didn't plot out a route beforehand. Had I planned that summer, I certainly would not have anticipated a farmer stint in Oregon, or becoming a freelance cartographer and making maps from a makeshift desk in the back of an old schoolbus. Three months after setting out, I crossed the land border into Canada on the opposite side of the continent and drove into the city so-called Vancouver.

For seven months I lived in Dunbar, a neighborhood of mostly wealthy single-family homes amongst which mine stood out. The backyard was a rambling garden bed with a sagging clothesline and blackberry briars that would catch my face and arms every morning as I pushed my bike through to the alleyway. Seven people and three hens lived there — a range of ages, personalities, and lifeworlds often in dissonance. This may come as a surprise but I didn’t research anything about the physical geography of Vancouver before deciding to move here. I don’t know why. Maybe feeling overwhelmed by multiple converging crises made indeterminacy sort of comforting. My only imaginary of Vancouver was from a glance at Google Maps’ Street View and featured images. Consequently, I was not prepared for the hills. Or the rain. Or even the mountains that backdrop the city skyline.

As a teaching assistant (TA) for a departmental cartography course, I was responsible for introducing and evaluating assignments, as well as demonstrating the use of required software. The first assignment: to make a map of downtown Vancouver by tracing a screenshot from Google Maps in Adobe Illustrator. (Adobe Illustrator is a proprietary illustration and graphics design software.) I marked sixty of these maps before I finally ventured to the place they represented.

My first excursion downtown was in December of 2021, six months after I arrived in Vancouver. I took the 7 bus from Dunbar all the way to downtown. This took about an hour — one reason downtown seemed so distant and therefore inaccessible from where in the city I was then living. My journey was prompted by a term paper I was stuck on. I thought going somewhere I hadn't been before would shift my perspective enough to dislodge me from writer's block. Additionally, I believed facing my fear of the unknown would give me the confidence to persist in writing my paper even though I felt lost. So I rode the 7 bus down Dunbar Street until it turned right on 4th Ave. We continued east for about ten minutes and then looped onto the Granville Bridge which carried us over False Creek and into downtown. I waited a few more stops before stepping off just after Waterfront Station. Still walking in the same direction as I'd been traveling, I came upon a bridge — an infrastructure which has supported my intertwined intellectual and pedestrian practices ever since. Thinking with this navigation and encounter, I wrote the following which became the prologue to that term paper:

site 1 Where Main Street ends, at the boundary between Gastown and the Downtown Eastside, there is a bridge. Well it’s more of a ramp really that curls around so the road never ends but continues by a different name in a new direction. I found myself there the other morning, standing alone just gazing towards the North Shore Mountains. It was clear and cold and snow had settled over their jagged peaks in a perfect gradient. Before the mountains and directly below me spread a panoply of infrastructure — Vancouver’s Centennial Terminals. Tower cranes, gantry cranes, straddle carriers, forklifts, trucks, trains, train tracks, shipping containers, and pipes of iron and steel. Every dimension was in motion. Machinery moved slowly and methodically while humans moved in erratic zig-zags around the pavement. Some were operating the machinery while some machinery were operating themselves. As a train drew in below me I peered down to see the conductor watching the switchboard, prepared to take action in the event of system failure.

But what happens when the train is your argument and it fails to budge along the tracks you’ve set out for it to follow? In my case, I laid down too many tracks. I got so swept up in constructing the possible paths this essay could take that when I geared up to leave the station — to write it all out — I was immobilized by the tangle before me. Although a lifelong creative, my undergraduate background is predominantly in the physical sciences and so thinking and writing academically within the context of humanities and social science scholarship is new. The infrastructure of a bridge holds sound because it is built not from one side over to the other but from both sides at once. I want to act as a bridge between the arts and sciences and so, while keeping one foot grounded in geospatial information and technology, I have stepped towards a new shore (and country) to learn from another perspective. Since arrival, I have been all around disoriented and not at all adept. My ideas are sprawling and interconnected like Centerm shipyard. There is so much this city this class and these books have led me to unpack and explore. For now, however, I am taking one final title, turning in one final direction, and following a single train of thought to an end with the idea of infrastructure in mind.

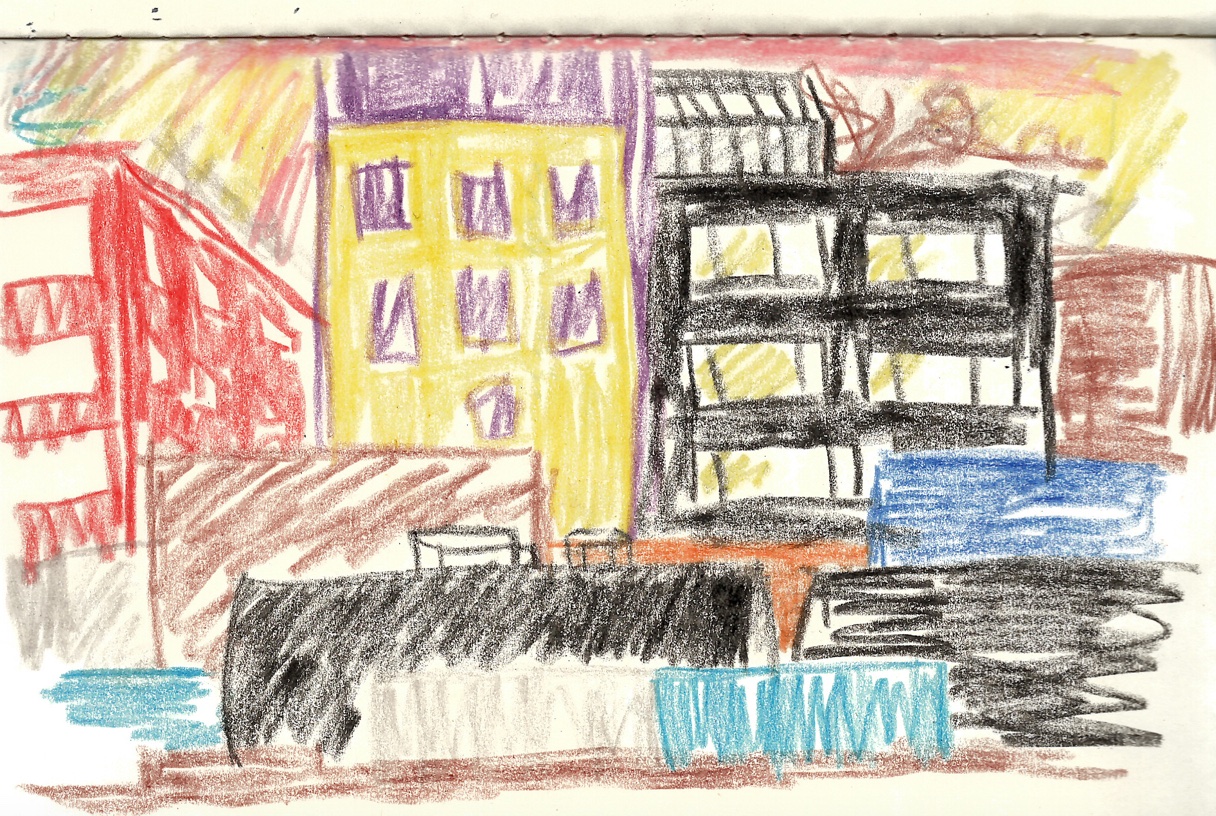

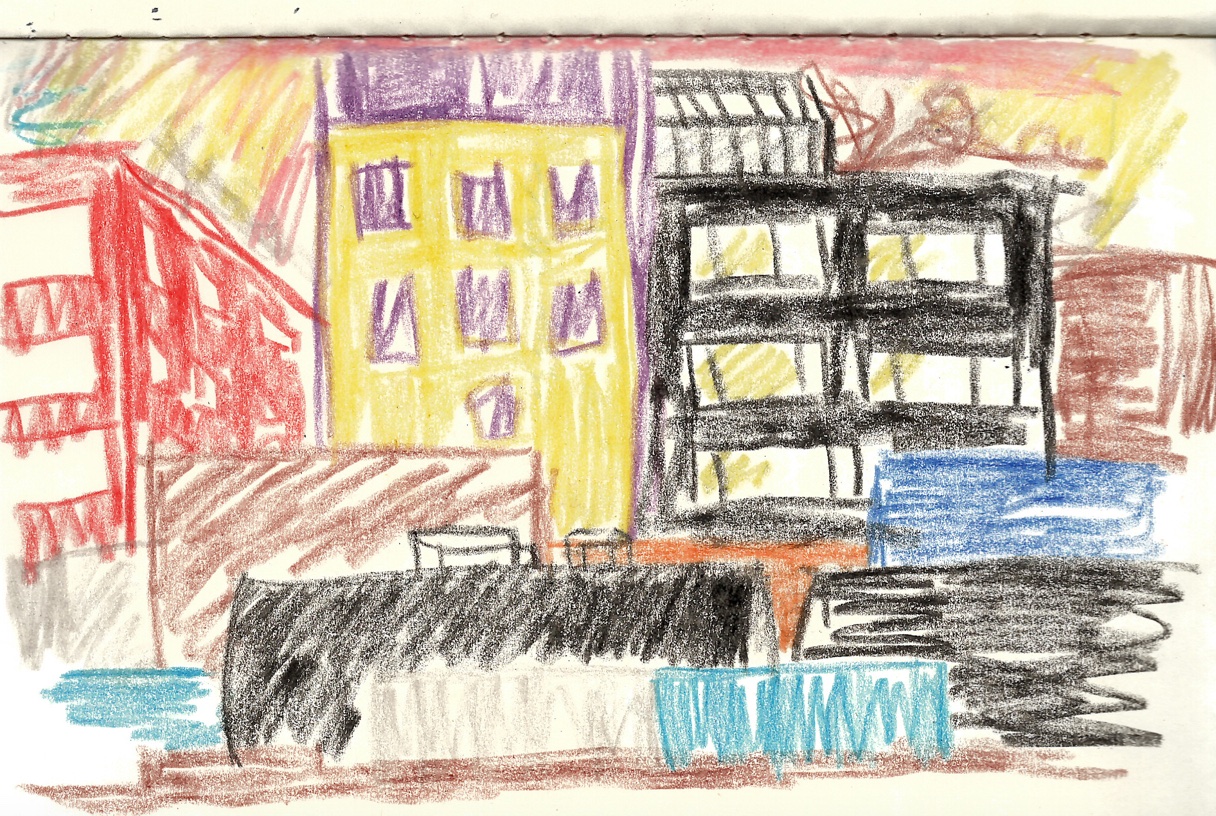

I returned to that place on new years eve and watched the sun set in silent company with 2 strangers who'd had the same idea. I walked along the back street and sketched the city from behind.

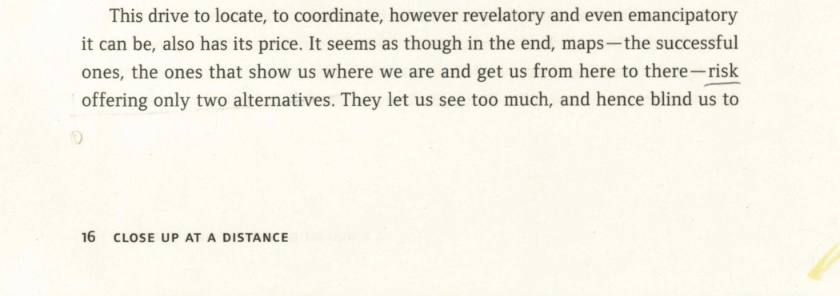

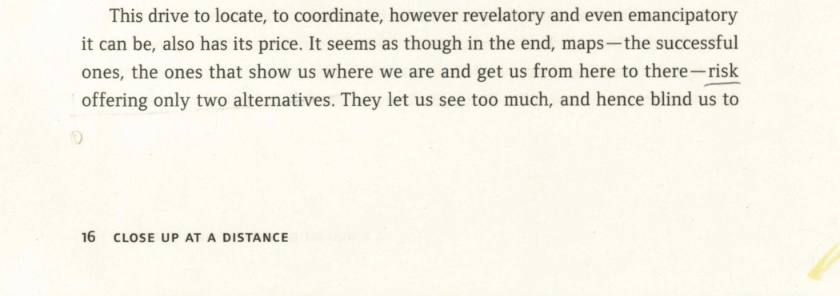

Having now inhabited Vancouver for three years and taught that first cartography assignment nine times, I find Google’s map incongruous with my mental map of the city drawn from practical, everyday experience. Such locative, destination-oriented maps, writes Laura Kurgan, “impos[e] a quiet tyranny of orientation that erases the possibility of disoriented discovery. . . ” (2013, 17).

site 2

site 2 from Kurgan, Laura. 2013.

Close up at a Distance: Mapping, Technology, and Politics. First hardcover edition. Brooklyn, NY: Zone Books.

Venturing to an unfamiliar area in order to help me write a term paper was my first explicit use of disorientation as a tactic. In that particular scenario, I intentionally disoriented myself in order to experience the physical sensation of becoming lost. And, without denying the affective registers of being lost, I remained open to the possibility of such a state also being generative of new ideas, connections, and perspectives. 'Disoriented discovery' (Kurgan 2013, 17) is then not necessarily without discomfort or even risk; perhaps the 'tyranny of orientation' (Kurgan 2013, 17, emphasis mine) is precisely that the comfort and safety Google Maps provides by orienting you in space at all times forecloses certain ideas, connections, and perspectives from taking shape.

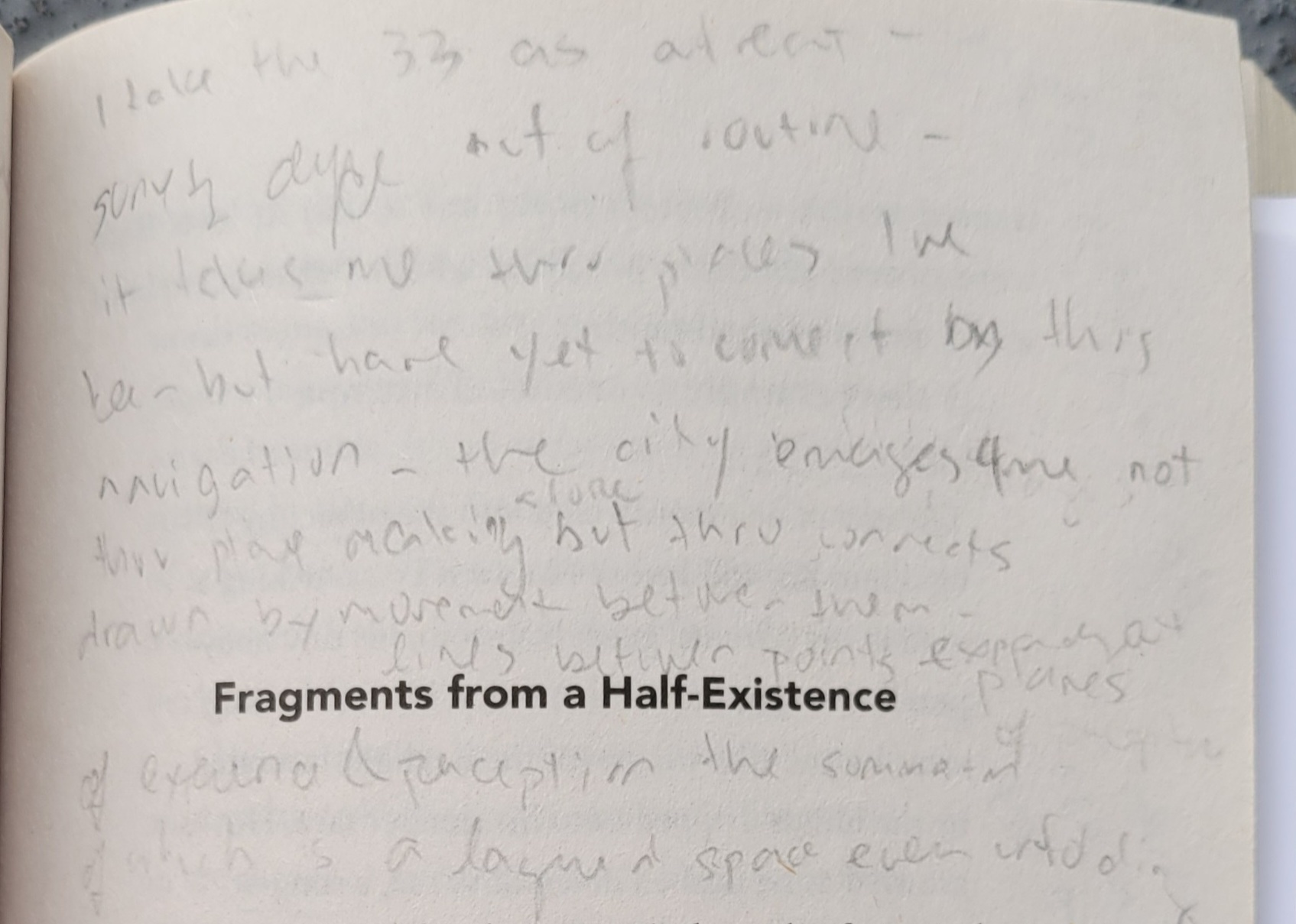

Indeed, spatial awareness of my surroundings has evolved (and continues to evolve) not by following Google Maps from A to B or memorizing the trace of its aerial contours, but rather as the effect of becoming lost and wandering around. Thus disoriented, I find areas of familiarity connected in surprising ways...

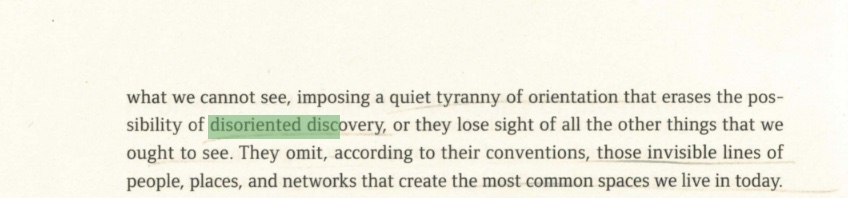

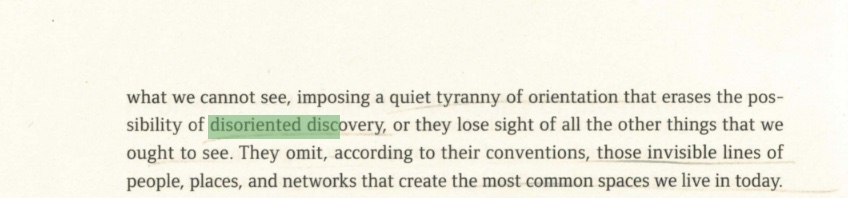

site 3 I take the 33 bus to campus on a whim. I'm running late to teach and I don't want to deal with the hassle of Broadway construction. Why have I never taken the 33? I wonder as a 5 minute walk brings me to a deserted stop. I sit on a bench in the sun to catch my breath. The 33 is one of the smaller buses. Its seats have that soft fabric patterned like a roller rink carpet. Riding the 33 is outside my routine. Its route takes me through places I've been before but have never connected by this navigation. I write (a version of) these thoughts in the white space of a book I brought with me to re-read —

A History of My Brief Body by Billy-Ray Belcourt.

Sometime later, I boarded the 99 B-Line with Critical Concepts for the Creative Humanities (2022). I had been in a rush to leave and grabbed it spontaneously from the pile of books on my kitchen table because it fit in my coat pocket and also because each concept is around a four page read — the time it takes to ride the 99 Bus 2 stops west along Broadway. The book opened in my lap to where I'd hastily tucked an IKEA crayon. A concept I'd been thinking about all day but had yet to visit in this book: Navigation. Write Tuin and Verhoeff (2022, 137): “...navigation entails the production of a performative cartography of a terrain, field, or domain that is constituted in the very act of its exploration." Exploration, put one way, is "the action of traveling in or through an unfamiliar area in order to learn about it" (“Exploration” n.d.). Though the field (be it a city, discipline, or body of academic literature) may at first be unknown and therefore unfamiliar, iterative navigations cohere a web of spatial relations that serve as reference. Such an open-ended, provisional topology in ongoing re/configuration is how I conceive of a mental map. Unlike Google’s 2-dimensional map that directs navigation from A to B, mental maps are composed (and decomposed) through nonlinear — even destination-disoriented — navigations that form "those invisible lines of people, places, and networks that create the most common spaces we live in today" (Kurgan 2013, 17). In The Practice of Everyday Life (1984), Michel de Certeau avers:

It is true that the operations of walking on can be traced on city maps in such a way as to transcribe their paths (here well-trodden, there very faint) and their trajectories (going this way and not that). But these thick or thin curves only refer, like words, to the absence of what has passed by. Surveys of routes miss what was: the act itself of passing by…The trace left behind is substituted for the practice. It exhibits the (voracious) property that the geographical system has of being able to transform action into legibility, but in doing so it causes a way of being in the world to be forgotten. (97)

I am interested in exploring different ways of navigating the world and the entangled nature of trace and practice. Although the first cartography assignment I taught generated practical knowledge of Adobe Illustrator, it did not prepare me or my students to navigate the city from ground level. Tracing Google Maps stood in place of spatial practice. The cartographer remained positioned as a disembodied viewpoint, a voyeur “lifted out of the city’s grasp” (de Certeau 1984, 92). From the 110th floor of the World Trade Center, de Certeau (1984) gazes down at New York City and remarks of the spectator:

His elevation transfigures him into a voyeur... It puts him at a distance. It transforms the bewitching world by which one was "possessed" into a text that lies before one's eyes. It allows one to read it, to be a solar Eye, looking down like a god. The exaltation of a scopic and gnostic drive: the fiction of knowledge is related to this lust to be a viewpoint and nothing more…Escaping the imaginary totalizations produced by the eye, the everyday has a certain strangeness that does not surface, or whose surface is only the upper limit, outlining itself against the visible. (92)

Google Maps exemplifies those visualizing technologies which perform "the god trick of seeing everything from nowhere" (Haraway 1988, 581). Tracing google maps simply re-presents a "gaze from nowhere" (Haraway 1988, 581) whereby the producers of geographic knowledge remain unimplicated in, and therefore unaccountable to, the boundary drawing practices entailed in rendering an object of knowledge. Feminist objectivity, Donna Haraway argues, is not gained from a distanced and disembodied position but rather through 'situated knowledges': "The only way to find a larger vision is to be somewhere in particular…living within limits and contradictions of views from somewhere" (1988, 590).

In contrast to the satellite imaginary gained from a global positioning, the 'rhythmanalyst' immerses themselves in the world with all their senses: “he must arrive at the concrete through experience” (Lefebvre 2013, 32). Figured by Henri Lefebvre (2013), the rhythmanalyst is he who “garbs himself in this tissue of the lived, of the everyday” and, taking his own internal rhythms as reference, comes to listen to the city as if it were a symphony (31-32). Situated simultaneously inside and outside their subject of analysis, the rhythmanalyst understands that “...to grasp a rhythm it is necessary to have been grasped by it; one must let oneself go, give oneself over, abandon oneself to its duration” (Lefebvre 2013, 37, emphases in original).

Pressing my chest against the Granville Bridge I feel at once its trembling vibration and my own heart’s rapid beating. I embody a sonic superposition: vibrational waves overlap; interfere; combine. The rhythm of their resulting wave marks a pattern of interference, also called a diffraction pattern. Through visceral encounter, I become entangled with the infrastructure which I had heretofore approached only as instrument unto an abstracting vantage. I realize the city is not a site with boundaries and properties whose determinacy preexists encounter and which I, as inhabitant-geographer-cartographer, may irresponsibly separate myself from in order to map from a distanced, exterior position. Rather, the city is performatively constituted as a physical-conceptual field whose emergent topology is iteratively drawn through everyday navigations and encounters. As such, the city of my inhabitation and I are entangled, figured and continuously reconfiguring in dynamic relation.

What could it mean to think with place? To feel the city?

My master’s research is an exploration and response to these questions through deep mapping, a practice of situated, embodied inhabitation by which I enter into dialogue with my surroundings. Deep mapping eludes operationalization in its interpretive capaciousness (Roberts 2016; Modeen and Biggs 2020), though disorientation is an excellent state in which to begin. To allow oneself to be grasped requires surrendering agency as a property of the individual. It entails an openness to defamiliarization, an attention to alternate perceptual scales, a porosity to "affect and to be affected" (Stewart 2011, 452). It requires caring to get to know a place through living and being: “deep mappers… immers[e] themselves in the warp and weft of a lived and fundamentally intersubjective spatiality" (Roberts 2018a, 51). Deep mapping does not render down to a map in the sense of a Cartesian cartography, where action is made legible by the substitution of trace for practice (de Certeau 1984, 97). Yet, neither does deep mapping ‘counter cartography’ (see Mason-Deese 2020) in the sense that it is not defined through opposition. Rather, in my theorization, deep mapping is marked by iterative acts of interference with hegemonic forms of representing place, producing geographic knowledge, and rendering My thesis project has amounted to cultivating a practice of deep mapping, theorizing my interpretation of this capacious practice through practice, and enacting my theory as praxis.

I submit to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies (GP+S) at the University of British Columbia (UBC), in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the degree of Master of Arts in Geography, the file ubc_2024_november_crandalloral_lily_negative_spaces.zip. Along with this, I submit a brief .pdf document containing metadata and instructions on how to download and unzip the compressed folder. The contents of this document, my thesis front matter, are rendered by the index.html page of this website. negative-spaces, the unzipped folder, contains the .html documents which, once read by web browsers, comprise what’s read by browsers of my webbed site. negative-spaces also contains the Cascading Style Sheet (.css file) responsible for the rendered look and feel of my website, as well as multimedia organized into subfolders.

negative-spaces is a webbed site, itself a space for deep mapping, for nonlinear exploration following ideas that grasp and pull the visitor. For evaluating supervisors and those desiring a guided tour, I have ordered the menu navigate elsewhere>>, located at the upper-left and bottom-left corners of every page, by my recommended navigation. My argument unfolds across six pages as follows: negative-spaces/disorientation.html introduces my research questions, aims, and the importance of learning through disorientation; negative-spaces/practice.html thinks through practice towards the formulation of a theory of deep mapping; negative-spaces/interference.html further elaborates on my theorization by situating it within a theoretical and methodological framework of diffraction; negative-spaces/tactics.html describes my tactics of practice and how they interfere with hegemonic economies of knowledge production in ways that 'matter'; negative-spaces/rendering.html demonstrates how making space for deep mapping renders theory as praxis; negative-spaces/superposition.html acknowledges that many stories exist in the landscape, this being but one whose determinacy necessarily excludes all other possible configurations. negative-spaces/rhythmanalysis.html is a collection of rhythms and patternings that exceed measure. You will notice two additional links at the bottom of navigate elsewhere>>. FRONT_MATTER will bring you back to the index.html page. CODE_SIDE will open a new page that displays the code that structures and formats the contents of the page in negative-spaces. This code-side view is hosted externally by the platform Github, and therefore not technically part of my submitted thesis. If you have a source code editor (like Visual Studio Code) installed on your personal computer you can open any of the .html documents with this software and view the code-side locally in this manner. What is rendered publicly visible by negative-spaces is not a substitute for my interference practice. Rather, negative-spaces — my thesis — is a partial account of an ongoing and open-ended interference praxis.

LEARNING THROUGH DISORIENTATION

We live in a moment where locative technology is ubiquitous. Becoming lost no longer requires going out of one's way. Instead, 'disoriented discovery' (Kurgan 2013) begins with a choice to not reference Google Maps, to turn location off and allow position to remain indeterminate.

site 4 One day I biked to Lighthouse Park, 30 kilometers each way. I decided not to use a navigational map and just find my way there. I biked through downtown and took the water taxi across Burrard Inlet to Lonsdale Quay, from where I leisurely made my way over many hills to Lighthouse Park in West Vancouver. On my way there I took my time biking around neighborhoods, getting a sense of the area. In one cluster of houses it seemed I'd entered a cul-de-sac and was caught in a loop, meaning I'd have to backtrack to continue on. But I had a feeling there would be a pathway somewhere. Sure enough, between two houses (well, parcels of private property, really) was the slimmest trail which opened onto a path that ran a great distance between two neighborhoods.

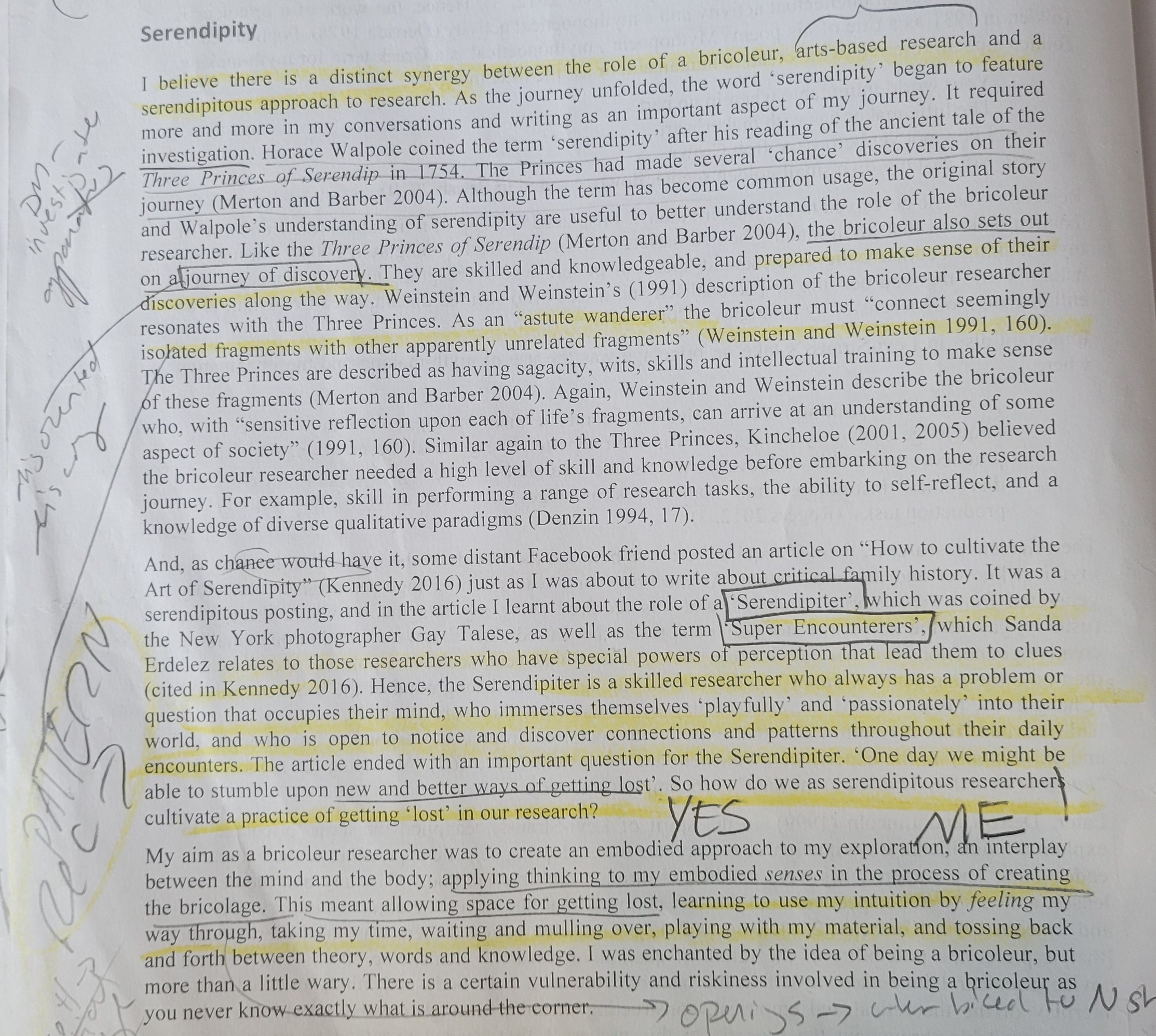

Detours open up the possibility of surprising connections and serendipitous encounters. Drawing on serendipitous encounters with the lure of serendipity itself, Esther Fitzpatrick (2017) describes the important role serendipity plays in her creative research practice. The Serendipiter, Fitzpatrick learns, “is a skilled researcher who always has a problem or question that occupies their mind, who immerses themselves 'playfully' and 'passionately' into their world, and who is open to notice and discover connections and patterns throughout their daily Encounters” (2017, 64). In this way, the Serendipter is not dissimilar from the rhythmanalyst or the deep mapper. Fitzpatrick articulates a kinship between the Serendipitor and bricoleur. For Fitzpatrick, being a bricoleur researcher means “allowing space for getting lost, learning to use my intuition by feeling my way through, taking my time, waiting and mulling over, playing with my material, and tossing back and forth between theory, words and knowledge” (2017, 64, emphasis in original). Deep mapping is slow scholarship in practice: it takes time to get lost, to make detours, to move forward with only an intuitive sense of a future opening. Les Roberts (2018b) writes that the 'researcher-as-bricoleur'

is arguably less governed by an overarching awareness that they are embarked on a ‘project’, and that, correspondingly, they are performing in compliance with a clearly defined set of ‘aims’ or ‘objectives’. The idea that research might be conducted under conditions of aimlessness and without a clear objective in mind does not necessarily mean that it lacks the rigours of ‘accomplishment and execution’ but that much of what is fashioned in the process is contingent on factors that cannot always be foreseen. (3, emphasis mine)

Scroll to view excerpt from Fitzpatrick, Esther. “The Bricoleur Researcher, Serendipity and Arts-Based Research.” Ethnographic Edge 1, no. 1 (December 7, 2017): 61–73. Right-click image and choose "Open Image in New Tab" to view enlarged version.

In destination-oriented research, an aim might be interpreted as an objective or output to work towards. But what if research aims were refigured as lures? Destination becomes more open-ended, with the journey becoming part of the research. Navigation might be expressed as the pursuit of a gut feeling or moving towards a sensed (but not seen) opening, following the drift of a graffiti tag or allowing oneself to be tugged and pulled by affective contours — a sidewalk dappled with sunlight, an inviting cluster of houses, the smell of California lilacs. In such dérives I am inspired by the Situationists (see Debord 1958). If "the bricoleur sets out on a journey of discovery” (Fitzpatrick 2017, 64), then unforeseen factors emerging from process impel the bricoleur-as-researcher, to swap Roberts' (2018b) configuration to suit myself. “The process is practice” observes Melora Koepke (2015, 156). Thinking with local practices of salt collection on the west coast of Vancouver Island evokes for Koepke a 'pedagogy of moments': "an expanding notion of the 'fields of possibility,' one that is oriented away from the 'result' or 'training' as an end destination. If this conception of an education has a goal, it is the receding horizon of fixed subjectivity” (2015, 161). The objectives of my research and the object of my thesis have emerged through everyday practices of talking, reading, and otherwise navigating a physical-conceptual field that was at first unfamiliar. I did not embark upon my thesis with a destination-oriented strategy so much as the desire to find out what being a geographer could mean for me. Instead of preemptively delimiting a field whereupon to lay my claim, in true relationship anarchy style, I designed my own commitments so as to “build for the lovely unexpected” (Nordgren 2006). My work is research-creation for it sets up a dialogue with the world and is driven by spatial and intellectual topoi which lure me forwards even before I comprehend where they lead (Loveless 2019). Research-creation, which is elaborated across the pages that follow, is about learning through disorientation… it “follows desire, and builds spaces and contexts that allow the time and space to experiment in unpredictable directions” (Loveless 2019, 70, emphasis in original).

Relinquishing "fixed subjectivity" (Koepke 2015, 161) and the "lust to be a viewpoint" (de Certeau 1985, 92) is not easy. Indeed, looking down from above things are less messy, more ordered, less mobile, more easily apprehended.

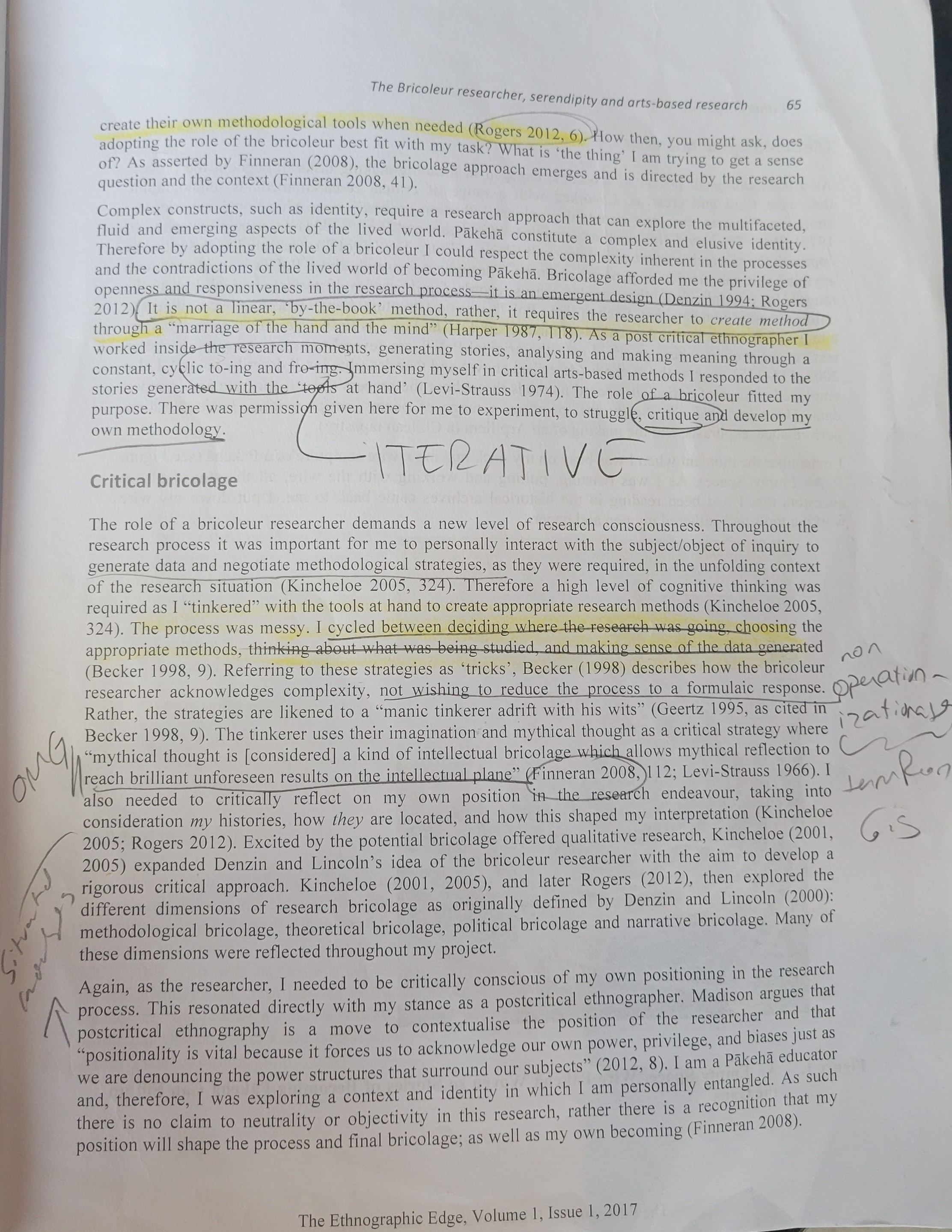

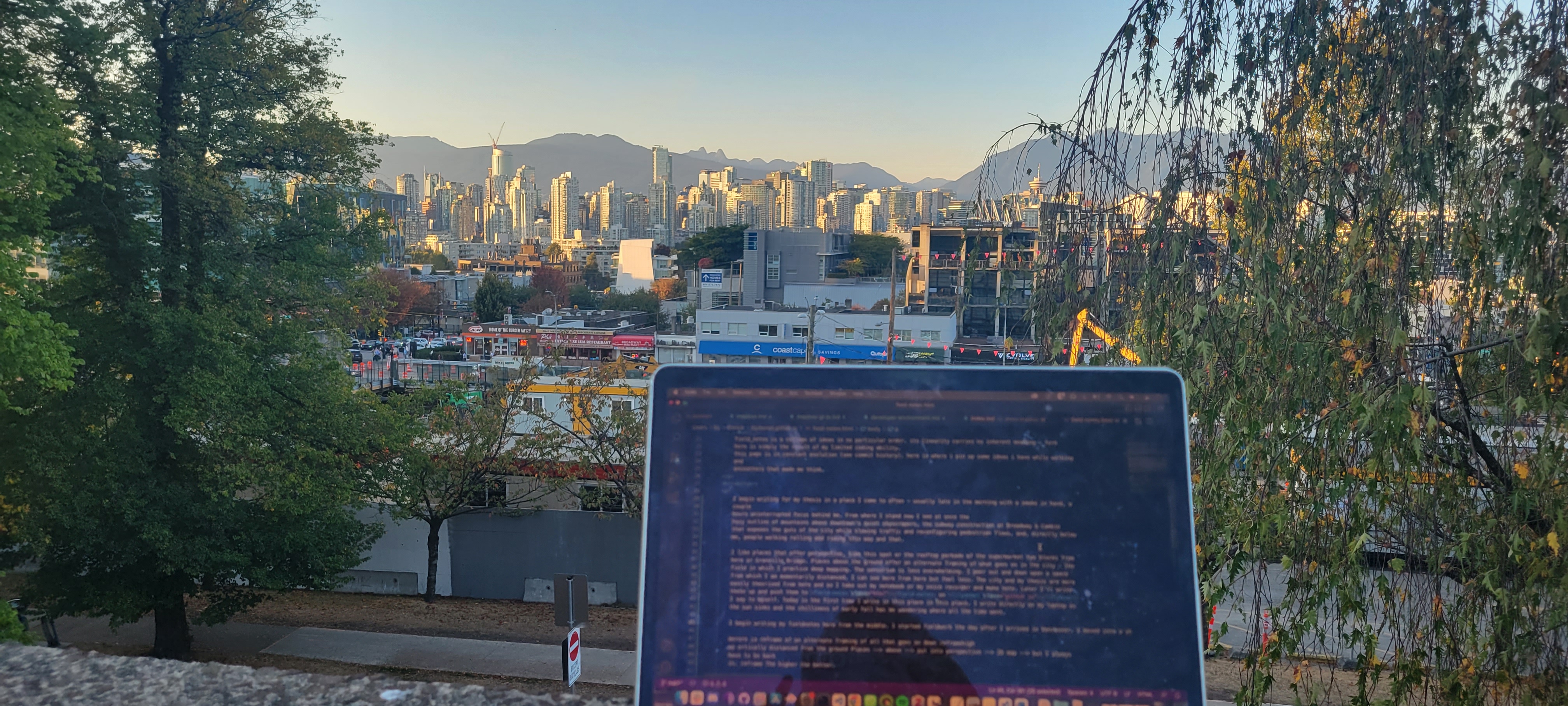

site 5 I begin writing for my thesis in a place I come to often — usually late in the morning with a couple hours uninterrupted thinking behind me. From where I stand now I see at once the hazy outline of mountains above downtown's quiet skyscrapers, the subway construction at Broadway & Cambie that exposes the guts of the city while slowing traffic and reconfiguring pedestrian flows, and, directly below me, people walking rolling and riding about their day.

I like places that offer me perspective, like this spot, or the rooftop parkade of the supermarket two blocks from here or Granville Bridge. Places above ground level offer an alternate framing of what goes on in the city — the field in which I practice deep mapping. The sensorium is less overwhelming up here. Less abrasive. Bodily distanced, I feel less. Vertically distanced, I see more. The places I have Been fall into some geospatial context.

Friday September 30th 2022

450 days of being here

Risking disorientation — not knowing where (in relation to the known) you are — is disconcerting. Becoming lost can feel scary. Probably my first sensation of being lost was in 2013, when I lived in Istanbul for four months while visiting my grandmother. At 14, this was the first time I had left the United States and the first time inhabiting a city of 15 million. Without Google Maps, I was solely responsible for navigating my mom and me around using paper maps and memory. In a short story I wrote about the experience I said:

site 6 My planning became fanatical: schedules and destinations made me confident. However, once, on our way back from the Süleymaniye Mosque, I forgot my map and we got lost. Night began to fall and we found ourselves threading through back streets, unable to find the main road by which we came. I panicked, my palms sweaty as I frantically, desperately, searched for something familiar. The alleys twisted crookedly back upon each other in the darkness causing all sense of direction to be lost. While it seemed like forever, barely half an hour elapsed before we found the busy sidewalks bordering a well lit street. My fear abating I thought, here I am again, wanting only to explore places I have already been, for fear of the unknown.

Excerpt from Ancient City, 2013

a short story by the author

Writing through disorientation is another beast. As I began configuring my thesis, I realized the entire story of my research could be differentially narrated through the framing of each page. Where to start and where to end, what to include and exclude — these exercises in boundary making began to feel like cruel and impossible tasks, so uncomfortable it was at times difficult to stay seated. It has helped to think of (and write) each page as a provisional configuration of ideas, where each page is articulated through dialogue with every other. Of course, this too led to disorientation.

site 7 Nothing is where I left it. I get up for a walk or eat or rest and when I return the words are there but I've forgotten what they meant. Is my thesis just writing about writing a thesis? Or doing fieldwork? I know I thought it all meant something yesterday. I felt it, at least. I had six ideas before noon but then I read the last chapter of this book and now I'm not so sure what matters. Is it all quite simple and elegantly connected from the start? Or is it a tangled snarl of threads which no amount of 'good' writing can unravel. Topology shifts with something so slight as a bikeride along an unfamiliar route. The city and my framework rearranges ever so little, coheres, connects back to something last visited a year ago.

My working memory can hold no more than four things at a time which makes writing a thesis where everything is connected and also layered and happening all at once very challenging. I don't think one sentence at a time. I feel ideas and their connections, wake up with wor[l]ds in my mouth, then iterate through phrasings until I land on an arrangement of words and punctuation that best approximates the feeling. And then I write around this grain until something is said. Oftentimes, I accidentally write something I never thought of before but which makes total sense. I'm trying to practice writing around nothing (yet) — not waiting for the grain between my teeth to start writing but just saying whatever's on my mind when I feel stuck and seeing if it goes anywhere. It's all possibility before you begin — every feeling a language in the process of becoming.

Early summer, 2023

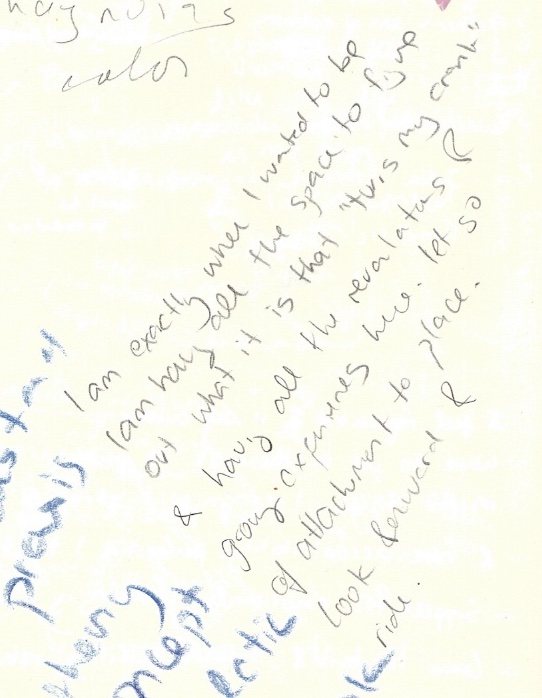

Learning through disorientation means embracing (or accepting, to begin with,) the challenge of navigating what is unfamiliar. I have learned that being lost is not so much the absence of direction but an opportunity to attune to the process of becoming familiar. Perhaps the very state of 'being lost' is relational. If your aim is disoriented discovery, then purposefully wandering into as yet unfamiliar realms has more to do with finding your way than losing it. Disorientation makes possible encounters and connections otherwise unlikely under the 'tyranny of orientation' (Kurgan 2013). For me, having completed a Bachelor of Science in physical geography and intending to pursue a PhD, there is something about this degree — a Master of Arts — that lends itself as a time and space for being all around disoriented, to "cultivate a practice of getting ‘lost’ in our research" (Fitzpatrick 2017, 64), and find ourselves lured in unpredictable directions by unforeseen factors.

site 8 I am exactly where I wanted to be/ I am having all the space to figure out what it is that "turns my crank" [as my co-supervisor says] and having all the revelations and growing experiences here. let go of attachment to place. look forward and ride.

My thesis is process rather than destination oriented. It emerges from navigating the field of possibilities opened up when A and B are recognized to be but place holders like latitude and longitude. "Every exit is an entry somewhere else" says an unsigned mural nearby my favorite brewery. As illuminated by negative-spaces/practice.html, the iteration of a form reveals beginning and end as merely places of turning and return.