Learning a tune from ear on the viola during a break

from Lefebvre, Henri. 2013. Rhythmanalysis: Space, Time and Everyday Life. Translated by Gerald Moore and Stuart Elden. Bloomsbury Publishing Plc. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781350284838.

GRANVILLE BRIDGE

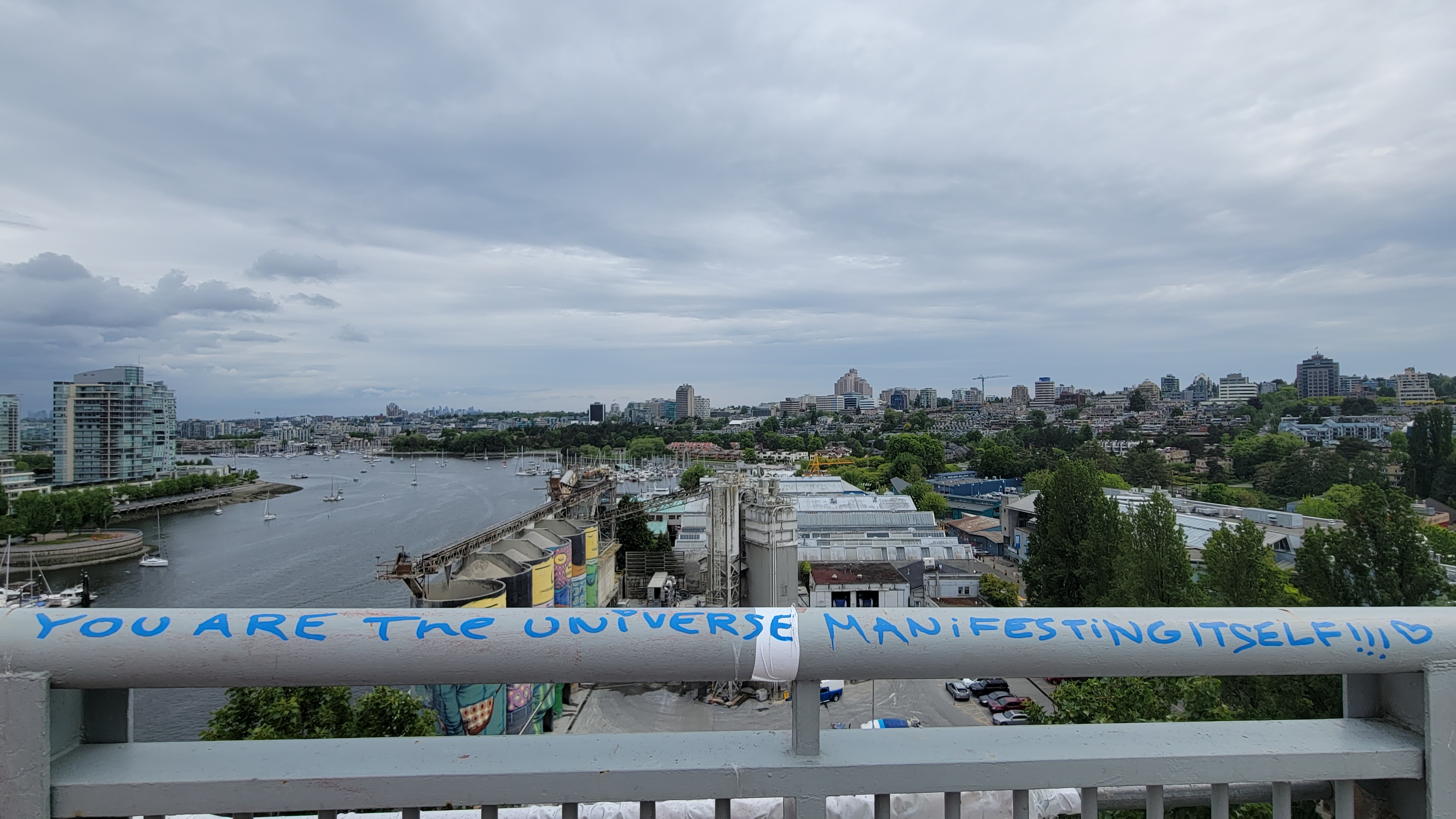

Pressing my chest against the Granville Bridge I feel at once its trembling vibration and my own heart’s rapid beating. I embody a sonic superposition: vibrational waves overlap; interfere; combine. The rhythm of their resulting wave marks a pattern of interference, also called a diffraction pattern. Through visceral encounter, I become entangled with the infrastructure which, heretofore, I had approached only as an instrument from whose abstracting vantage I could conduct rhythmanalysis of the field below.

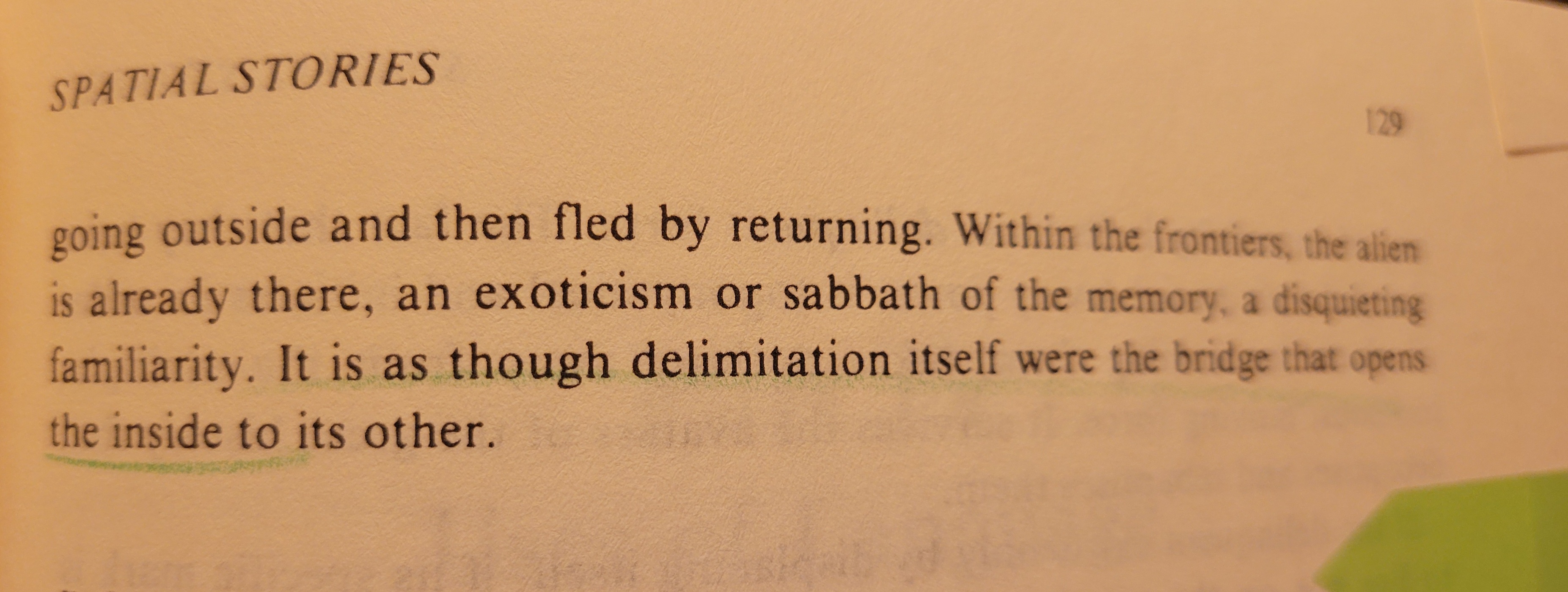

from de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

from de Certeau, Michel. The Practice of Everyday Life. Translated by Steven Rendall. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1984.

.jpg)

THERE'S A NEW ANIMAL IN TOWN In January 2023 I first became aware of the Amazon Van’s backup sound. It’s unlike any vehicle beep I’ve ever heard. Short and aggressive, it's like the grunt of a rooting pig. Or the cry of a Steller's jay. It’s so distinctive that no matter how far away the van and faint the sound, my ears will sense it and immediately associate sound to source. I involuntarily think of Amazon like 6 times a day now.

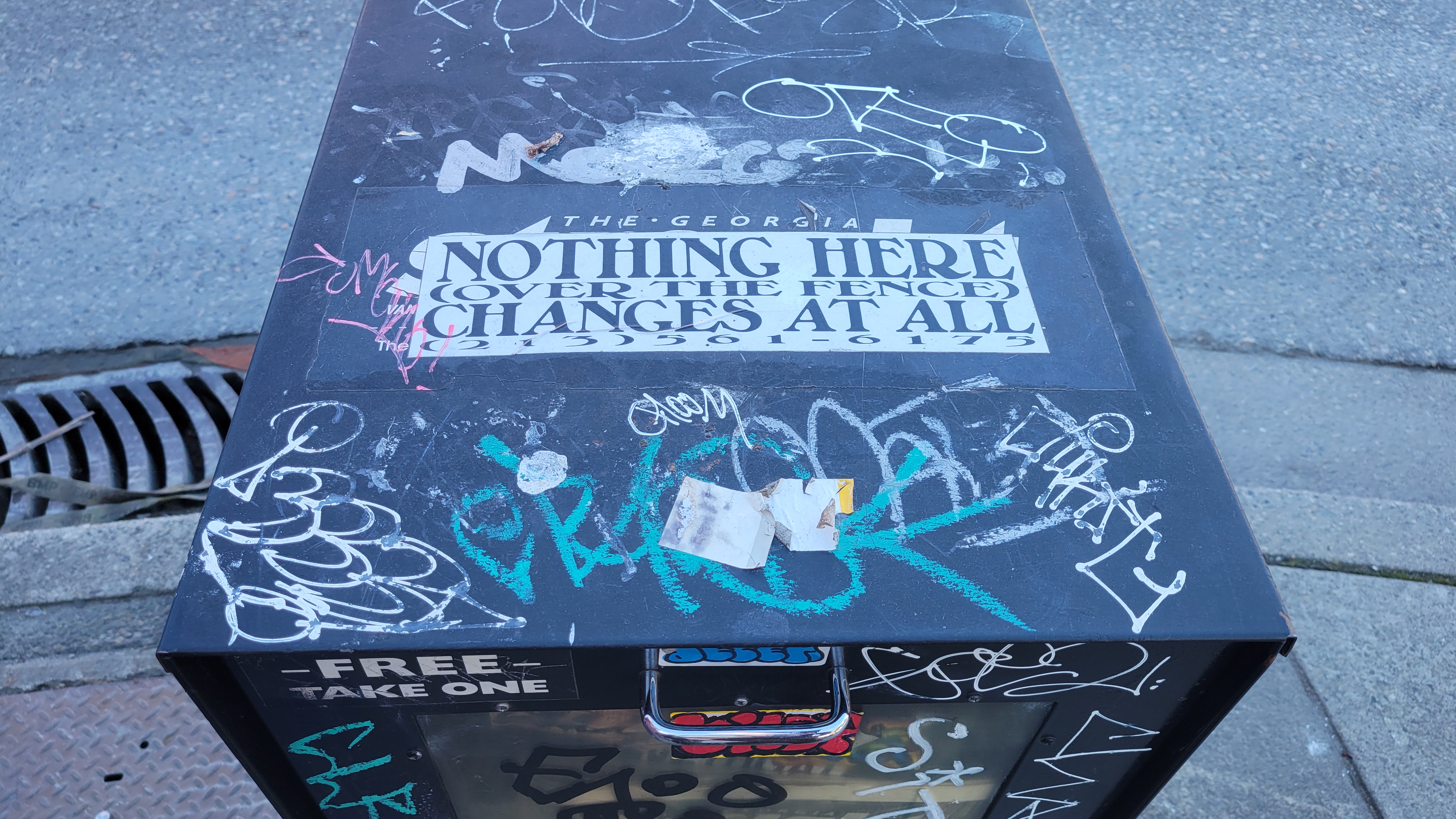

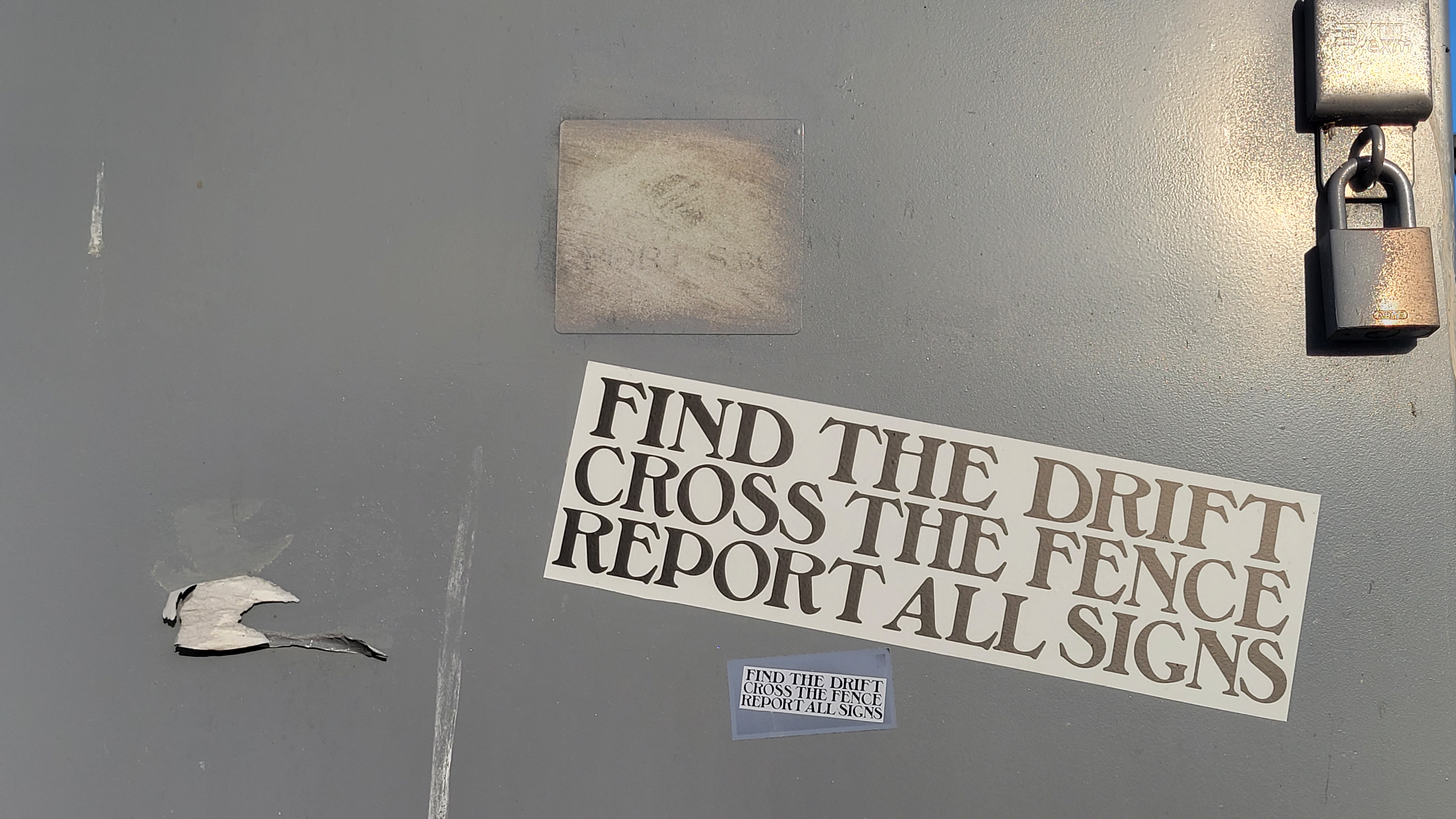

SIGNS OF PROTEST

"The critical power of graffiti lies in its surfacing: it ruptures the processes of political edification and it frames the situated surfaces of specific edifices upon which it makes its marks." — Avramidis 2023, in Place writing, site drawing

Much of my fieldwork has involved navigating Vancouver, my empirics emerging as inextricable layerings of sensorium, affect, and infrastructure. Alongside practicing and theorizing deep mapping, during my thesis research I have worked as a Teaching Assistant for a departmental cartography course, completed GIS research assistance, and performed freelance cartography. I also continue to work in the university library Research Commons, where I teach and consult on geospatial matters as well as develop and/or facilitate workshops on mapping and geographic information systems (GIS). One of the workshops I led last summer was on building walkability indexes with QGIS (“Network Analysis,” n.d.). Geospatial data are data for which a locational property, such as coordinate or street address, is measured. A walkability index is a quantitative assessment of the relative accessibility of amenities within a delineated area. The library's workshop assumed as its empirics geospatial datasets which render the city down from above as a collection of points, lines, and polygons. Indeed, it was possible to make the index without any reference to on-the-ground, everyday navigations. Given geospatial data representing Vancouver's city blocks, population density, and amenities, GIS provides the tools to analyze proximity and connection, as well as visualize the result through a map.

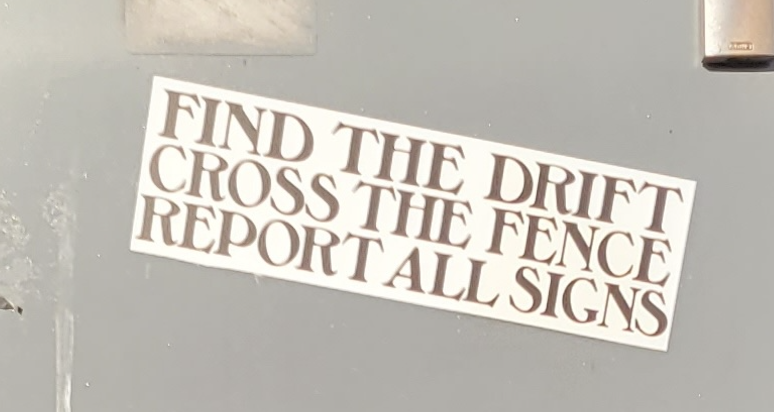

Around the same time as I was preparing the walkability workshop, I began noticing these '15 minute City Ready' stickers popping up along the Vancouver greenway, a stretch of the old Canadian Pacific railroad that's been transposed into a designated pedestrian and bike path. Conceptualized by city planner Carlos Moreno, the '15 minute city' is the idea “that cities should be designed or redesigned so that, within the distance of a 15-minute walk or bike ride, people should be able to live the essence of what constitutes the urban experience: to access work, housing, food, health, education, culture and leisure” (Moreno 2020). Over the course of the spring, more stickers appeared, pasted over DO NOT ENTER EXCEPT BICYCLES signs and those yellow/black striped hazard markers. At the same time that the stickers began proliferating east, west, and even across the bridge into downtown, they also began being scratched off. Reapplication, however, was swift. Then I sighted something different: at first one then two sites, scrawled in blue sharpie over '15 minute City Ready' was the declaration RESIST.

But resist what? Well it turns out the '15 minute City Ready' stickers are actually in protest of the ‘15 minute city’ — the decal’s chain-link background representing enforced limited mobility. I sighted the first sticker just days after being introduced to the ‘15 minute city’. Conceptualized by Carlos Moreno (2020), “the idea is that cities should be designed or redesigned so that within the distance of a 15-minute walk or bike ride, people should be able to live the essence of what constitutes the urban experience: to access work, housing, food, health, education, culture and leisure.” This led me to think about how proximity and connection in the city are measured, imagined, and experienced. What are the processes of datafication that determine ‘input values’ and ‘walkability scores’? To the workshop’s description of network analysis I included the invitation to ponder: In what ways do walkability indexes render partial representations? Who and what is not accounted for by the data? The location and surface of the stickers' placement on bikeway signage is significant. The signification of protest comes to matter through the stickers’ material-semiotic interference with infrastructural boundary demarcations. City signs become palimpsests — sites of super/im/position signaling contested urbanisms.

Following the proliferation of these signs of protest, I began thinking about the ways spatial data are made differentially legible by technoscientific and affective orientations to engaging/representing place, producing geographic knowledge, and rendering spatial research public through maps and textual publications. The technoscientific and affective orientations I am specifically thinking about are Cartesian cartography and Geographic Information Systems (GIS) on the one hand, and sensory and embodied spatial methodologies/practices broadly construed on the other. This is not to say there is a clear demarcation between the two, that there are only these two orientations, or that either camp is homogenous. I have been a practitioner of both long enough to know this is not the case. Rather, I am interested in patterns of presuppositions – required postulates even – that differentially correspond to what's hailed as "top-down" or "bottom-up" mapping practices. How are empirics made legible as data by the apparatuses that produce them? How are technoscientific and affective orientations to ‘what counts as data’ co-constitutive of an empirical account of the city? I am particularly invested in how the apparatuses through which differential embodiment is constituted effect different possibilities for knowing. This is something I intend to further study through diffractive mapping during my PhD.

Early April 2022, Quinn and I are walking along a familiar street and see, resting amongst the regular fairy pebbles and kitsch that decorate the bases of so many chestnut trees in this neighborhood, a box of chalk. It’s an open-ended invitation to which we respond by pausing to draw colorful forms on the sidewalk. “Very affirming” comments a passerby as they smile and skirt around us. In this moment, we transformed an otherwise pedestrian space into a place of interest, using what mediums surround us to engage with the city and its passersby.

Days later we walked the same sidewalk and saw the weathered impression dissolving back to abstraction. I wonder how many soles picked up pieces of chalk and how far our art walked with them.

In the time after finding the first sign, before I begin encountering the admittedly more ominous ones, I made my own stickers. I stuck them nearby the first sign, and elsewhere around the city.

In the time after finding the first sign, before I begin encountering the admittedly more ominous ones, I made my own stickers. I stuck them nearby the first sign, and elsewhere around the city.

This spring, 2024, the first sign and my contribution were sadly taken down.

This spring, 2024, the first sign and my contribution were sadly taken down.

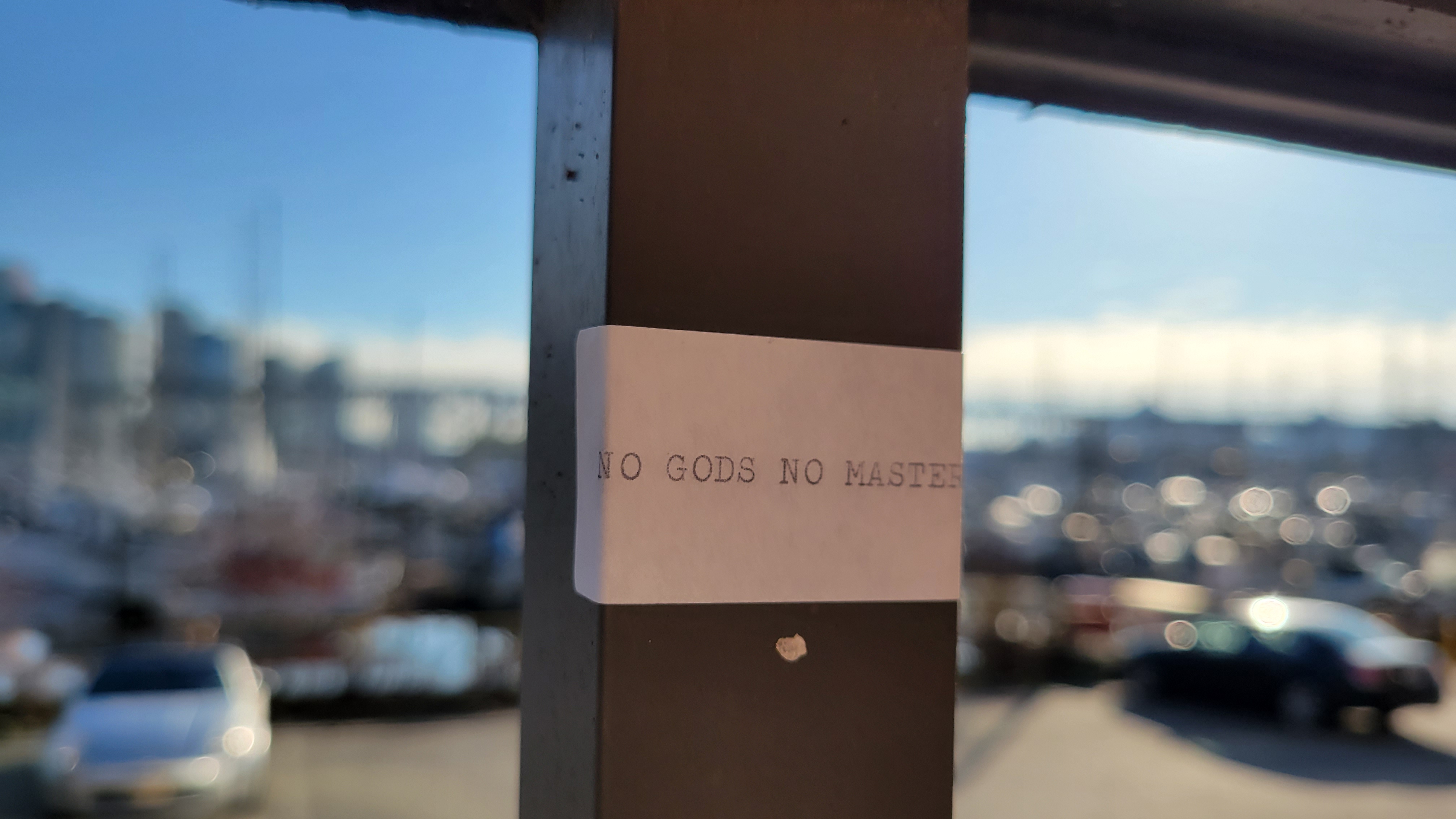

February 7th, 2024 — I had my first encounter during a walk around False Creek. On the pedestrian overhang above the Fish Market I noticed the little sticker between the metal railings: NO GODS NO MASTERS.

February 7th, 2024 — I had my first encounter during a walk around False Creek. On the pedestrian overhang above the Fish Market I noticed the little sticker between the metal railings: NO GODS NO MASTERS.

March 17th, 2024 — The following month I had my second encounter. On another walk, just beyond where I'd spotted the first sticker on a lamppost near the Museum of Vancouver: NO GODS NO MASTERS.

March 17th, 2024 — The following month I had my second encounter. On another walk, just beyond where I'd spotted the first sticker on a lamppost near the Museum of Vancouver: NO GODS NO MASTERS.

May, 2024 — at a crosswalk on my way to Greens grocers: free Palestine

May, 2024 — at a crosswalk on my way to Greens grocers: free Palestine

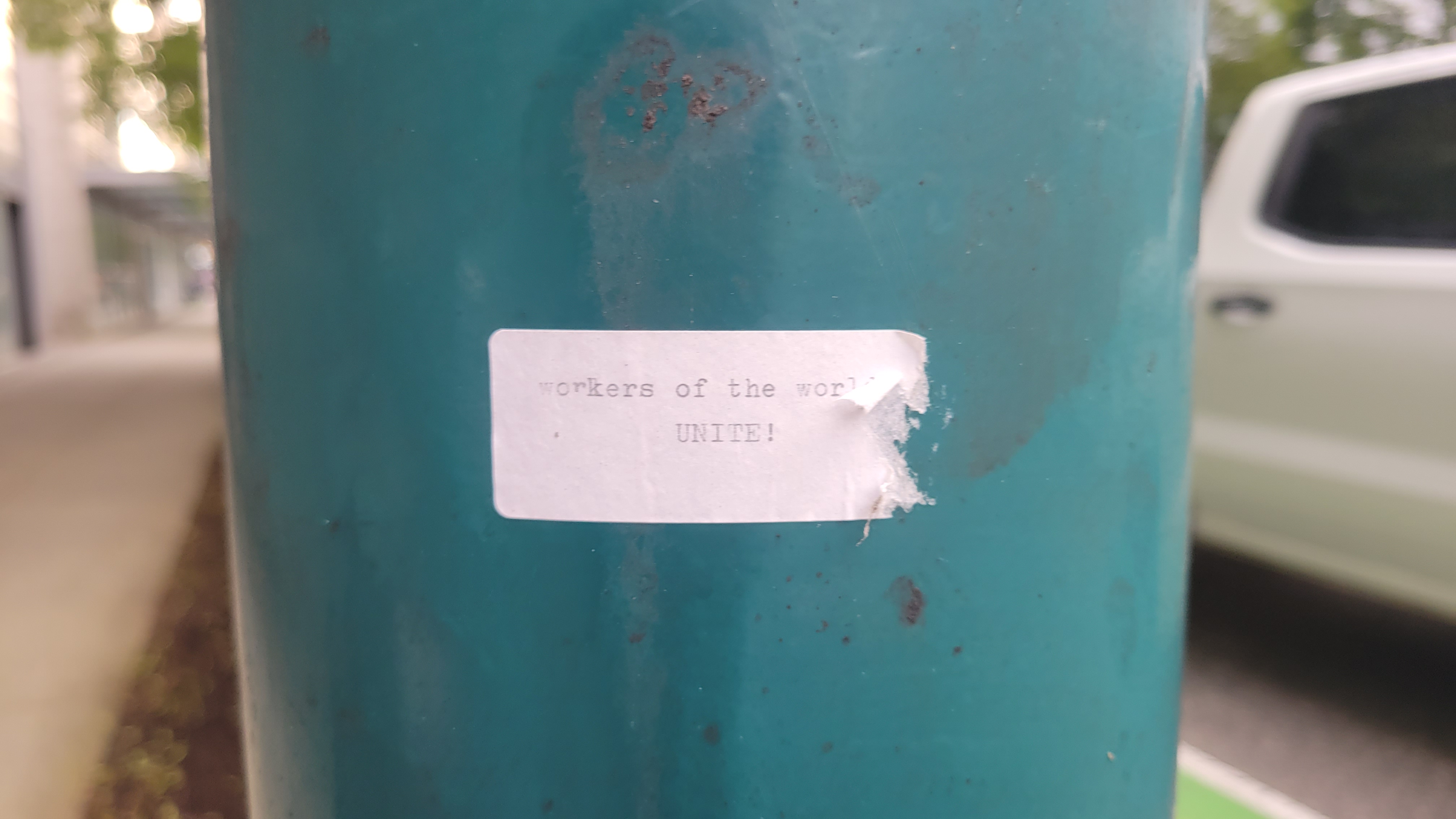

June 11th, 2024 — on a lammpost on my block: workers of the world/ UNITE!

June 11th, 2024 — on a lammpost on my block: workers of the world/ UNITE!

June 11th, 2024 — on a lamppost at the major intersection of 7th and Cambie: free Palestine

June 11th, 2024 — on a lamppost at the major intersection of 7th and Cambie: free Palestine

June 13th, 2024 — on a lamppost also near home: WORKERS OF THE WORLD! UNITE!

June 13th, 2024 — on a lamppost also near home: WORKERS OF THE WORLD! UNITE!

TRACING AS PLACING

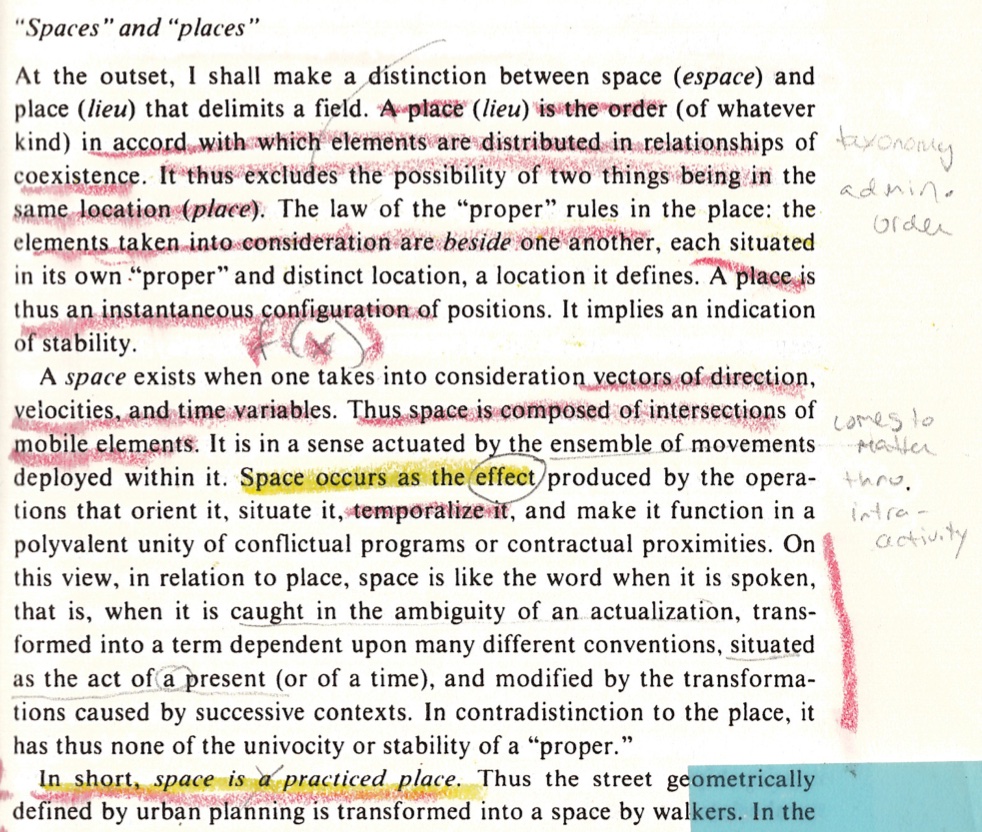

Reading Barad (2007) and de Certeau (1984) through one another, I believe place and space to be phenomenal expressions of the world differentially articulated through trace and practice. In The Practice of Everyday Life (1984), Michel de Certeau relationally articulates space and place with the following: "space is a practiced place" (117, emphasis in original). He writes,

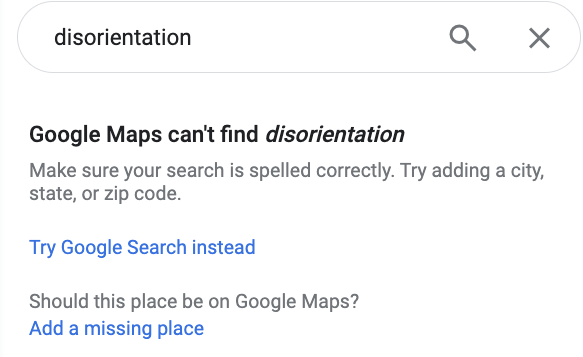

Google’s map of Vancouver abides by the law of the "proper". It produces the city as a place wherein each element has a distinct location. Position is made determinate by a spatial configuration which "excludes the possibility of two things being in the same location (place)" (de Certeau 1984, 117, emphasis in original). Such a static, Cartesian coordination allows for navigation to be routed (by Google) from one element to another. The navigational possibilities, however, remain determined (and constrained) by the law whose logic governs this map: follow streets, not alleys; walk on sidewalks; don’t jay-walk; turn right here, not at the next block. Disorientation is a destination not found by Google Maps, which asks in response, "Should this place be on Google Maps?" ("Google Maps" n.d.).

Yet de Certeau contends it is pedestrian movements that spatialize the city, writing, "space is composed of intersections of mobile elements…space occurs as the effect produced by the operations that orient it, situate it, temporalize it…" (1984, 117). While urban geographers and planners may theorize and design the city, urban space is produced through everyday navigations and encounters. If the apprehension of place renders position determinate, the motion that spatializes renders position indeterminate: "to walk is to lack a place" (de Certeau 1984, 103). Google Maps imposes the law of the "proper" upon navigation by substituting "a mark in place of acts, a relic in place of performances: it is only their remainder, the sign of their erasure" (de Certeau 1984, 35, emphasis in original). The relationship between place and space seems entangled with that between trace and practice. In negative-spaces/practice.html, I introduced the iterative spatial practices of eurythmy and form drawing I grew up practicing as part of Waldorf education. Each week, beginning in first grade, we would sit for an hour in silence drawing a single form over and over, our crayon in constant contact with the page. Writes form drawing teacher Rosemary Gerbert, "a form drawing is a present record of a past movement, the remaining trace of a finished gesture" (1987, 9). Tracing is a practice of (spatial) citation. Tracing is still practice. It is the trace which, once framed as the output, marks the effects of an interference practice and in so doing, renders the practice by which it was constituted unintelligible. Places, like objects of knowledge, are not preexisting entities but "boundary projects" (Haraway 1988, 595) drawn into being by boundary making practices such as tracing. If space, time, and matter are phenomena (Barad 2007), places are as well. Position may take on determinate values whose measurements refer to situated locations rendered intelligible within and as part of a place phenomenon. The source of the map produced through the cartography assignment I TAed was not Google Maps' aerial view of the city but rather the practices of tracing and exclusion which constituted downtown as an object of observation. Objectivity requires reference be made not (only) of Google Maps but the place phenomenon within which downtown Vancouver emerged as an object of knowledge.

We live in a moment where locative technology is ubiquitous. Becoming lost no longer requires going out of one's way. Instead, "disoriented discovery" (Kurgan 2013) begins with a choice to not reference Google Maps, to turn location off and allow position to remain indeterminate. I am particularly interested in how pedestrian tracings of Google Maps — a locative technology which renders the city down from above as a place — inform everyday navigations and thus the production of urban space. My future research will conduct further investigation into how Google Maps defines intra-actions between humans and urban infrastructure, becoming part of dialogue with the urban surround it both enables and constrains.